What is Deflation in Economics?

Deflation means persistently falling prices in the economy i.e. a negative rate of inflation. It usually occurs when consumer demand for goods & services has collapsed, and a severe recession has resulted.

In such circumstances a downward spiral in economic output can result. This is because firms will likely be forced to further cut prices, and reduce production, in order to reduce their inventories.

The cut in production will then imply job cuts since fewer workers are needed to produce fewer goods. Those job losses would further reduce consumer demand from an already low level, and so the downward spiral into a deeper recession begins.

Consumers will be reluctant to increase their demand for goods in these circumstances for two main reasons:

- Job losses, or the mere threat of losing a job, will make some workers either unable to maintain their usual level of spending, or much more likely to save money in order to protect themselves against future financial hardship.

- Falling prices in the current period can lower expected prices in the next period, and thereby encourage consumers to hold off on purchasing some goods today in the hope of being able to purchase them later at a lower price.

Deflation vs Inflation

At first glance it may seem like the economic circumstances which might lead to deflation vs inflation should be at polar opposites, because one is a state of persistently falling prices while the other is a state of persistently rising prices. However, these two scenarios are much more closely related than it appears.

The presence of either deflation or inflation in an economy, in any significant way, indicates that serious problems and a likely recession lie ahead. The big question relates to how the government and financial authority (i.e., the Federal Reserve Bank) will react to the threat of recession.

If a stimulus policy of discretionary fiscal spending combined with a loose monetary policy and lower interest rates is adopted, then inflation is more likely (assuming that there is a lack of spare capacity in the economy to accommodate the stimulus).

If, on the other hand, the government were to hold off on any stimulus spending and the Fed were to remain neutral, the recession would likely result in deflation because of the effect of job losses and falling prices as explained above.

This, of course, raises the further question of why the government and Federal Reserve would ever choose to stand idle in this situation rather than stimulate the economy. I will answer that question in the next section.

What Causes Deflation?

The real cause of deflation is economic necessity when a serious recession/depression is unavoidable. While it might seem like bad policy to allow a deflationary recession to occur, if the alternative is an inflationary recession then it may be the lesser of two evils.

Even the consequences of the Great Depression of the 1930s, when the unemployment rate in the US rose to almost 25%, were mild compared to the utter devastation wrought by the Hyperinflation in Weimar Germany a decade earlier.

The economic necessity for deflation arises after a prolonged period of unsustainable aggregate demand relative to aggregate supply. In a fiat monetary system with a fractional reserve banking system, combined with incompetent management of the economy, the potential for spending to exceed its long-run sustainable rate exists.

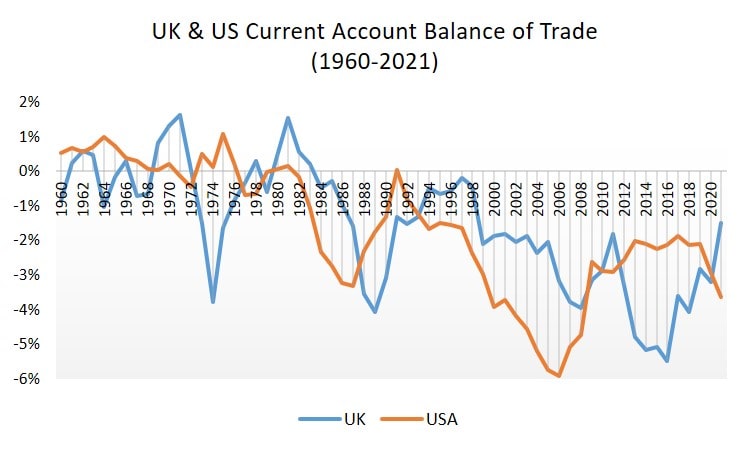

In fact, most of the western countries have been doing exactly that since well before the 2008 financial crisis. A strong case can be made to argue that the UK and US have tended towards excessive spending ever since the collapse of the Bretton Woods System in 1971. The money supply in both countries has expanded excessively with ever lower interest rates even as huge current account deficits in both countries have ballooned into existence.

During the same period, excessive fiscal spending by our governments has created levels of national debt that have never been seen before in modern peacetime history.

The financial crisis in 2008 was a wake up call, but it went unheeded. The policy ever since has been to prop up the system with growing budget deficits and even looser monetary policy.

By the time the Covid-19 pandemic hit, our economies were already approaching breaking point, but the policy once again was to stimulate with money-printing, near zero interest rates, and massive amounts of fiscal spending.

In the early 2020s the economic outlook is extremely bleak. Inflation has arrived and threatens to wreak havoc if left unchecked, but the only way to keep it in check would be to allow a huge recession that would create the circumstances for a deflationary depression.

If our governments cave in to pressure, and pivot too soon from their policies of raising interest rates to control inflation, then inflation will likely come roaring back with an even worse threat to our economies in the form of hyperinflation.

The necessity for deflation and a deep recession, in order to stop the endless descent into ever deeper debt, appears to be here. However, it would be a dubious proposition to suggest that our governments and monetary authorities have the fortitude to see it through. After all, it was their incompetence and self-interested short-term political motives that created this situation in the first place.

Deflation Example - The Great Depression

The best example of deflation occurred over the 10 years from 1929 to 1939, it was known as the Great Depression. As always with these things, the Great Depression was preceded by a period of excessive spending known as the roaring 20s, and the catalyst for that had been victory in World War 1.

Fueled by all the feel-good spending in the 1920s, the stock market had soared higher, but all that ended in late 1929. By September the Wall Street stock market crash had arrived, the point widely regarded as the start of the Great Depression.

The exact causes of the Great Depression are still a topic of much debate and disagreement among economists of different schools of thought today. But whatever the exact cause, the ramifications of the collapsing stock market led to panic, and a banking-run as people desperately tried to withdraw their money from the banks.

Unfortunately, in a fractional reserve banking system, only a small percentage of current account deposits are kept in vaults, most of it is loaned out to other customers. With withdrawal demands far in excess of anything that the banks could honor, more and more banks had to close their doors and declare bankruptcy due to insolvency.

Around 35% of the money supply in the US was destroyed as a consequence of failed banks and, with the dollar in short supply, prices throughout the economy started to decline as deflation took hold.

The government at that time was committed to a balanced budget, and so it did little to reflate the economy. Similarly, the Federal Reserve was not in the business of bailing out private banks, and so it allowed banks to collapse.

The end result was deflation, and a severe depression due to collapsing aggregate demand.

Keynesian economics was born out of the aftermath of the Great Depression, with the aim of demand management to try and smooth out the boom-bust business cycle. The suggestion there was that a free-market was too volatile if left to its own devices.

Proponents of free-market economics retort that if the banking sector had been free to set interest rates (instead of the Federal Reserve controlling them) then rates would have risen throughout the 1920s in order to encourage saving and discourage spending. In other words the fault lay with the Federal Reserve, not the free-market.

The boom that led to the depression could have been avoided with rising interest rates because the roaring 20s would not have seen such unsustainable amounts of spending in the first place.

The deflation of the 1930s saw prices fall by around 30-35%, similar in magnitude to the fall in the money-supply, and giving weight to the insights of:

Sources:

Related Pages:

- Debt Deflation

- Inflation Vs Deflation

- Are Tariffs Deflationary?

- Disinflation

- What is Inflation?

- What Causes Inflation?

- How to Stop Inflation

About the Author

Steve Bain is an economics writer and analyst with a BSc in Economics and experience in regional economic development for UK local government agencies. He explains economic theory and policy through clear, accessible writing informed by both academic training and real-world work.

Read Steve’s full bio

Recent Articles

-

What Happens to House Prices in a Recession?

Jan 11, 26 03:13 AM

What happens to house prices in a recession? Learn how different recessions affect housing, why 2008 was unique, and how policy responses change home values. -

Does Government Spending Cause Inflation?

Jan 10, 26 06:01 AM

Does government spending cause inflation? See how waste, crowding out, and stimulus spending quietly push prices higher over time. -

What Happens to Interest Rates During a Recession

Jan 08, 26 05:31 PM

What happens to interest rates during a recession? Explore why rates often fall, when they don’t, and how inflation, policy, and markets interact. -

Circular Flow Diagram in Economics: How Money Flows

Jan 03, 26 04:57 AM

See how money flows through the economy using the circular flow diagram, and how spending, saving, and policy shape real economic outcomes. -

What Happens to House Prices During Stagflation?

Jan 02, 26 09:39 AM

Discover how house prices and real estate behave during stagflation, with historical examples and key factors shaping the housing market.