- Home

- Circular Flow Diagram

Circular Flow Diagram

in Economics: How Money Flows

The circular flow diagram in economics shows how money flows between households, businesses, governments, and the financial system — and how changes in spending, saving, or policy ripple through the wider economy.

Although the diagram is often introduced early in economics courses, it is not just a teaching tool. It helps explain real-world outcomes such as why economic slowdowns feed on themselves, how government spending and taxes affect private activity, and why money can appear to “disappear” from some parts of the economy while piling up in others.

This article explains the circular flow diagram step by step, starting with the basic flows between households and firms before expanding to include saving, investment, government activity, and foreign trade.

The Basic Circular

Flow Diagram in Economics

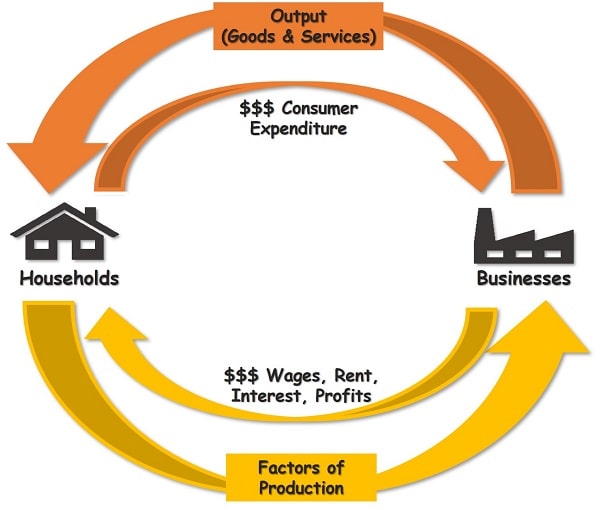

The basic circular flow diagram illustrates how households provide inputs i.e., factors of production, to firms in return for money and how that money flows back to firms through consumer spending on goods and services. This two-way flow is the core of how money circulates through an economy.

These flows of economic activity are indicated starting with the bottom yellow arrow in the circular flow diagram below, through to the top orange arrow respectively.

The basic circular flow model: households provide labor and other inputs to firms receiving income in return, which they spend on goods & services, illustrating how money moves through an economy.

The basic circular flow model: households provide labor and other inputs to firms receiving income in return, which they spend on goods & services, illustrating how money moves through an economy.In order to complete the basic model, we need to account for the saving and investment flows of households and businesses, the actions of government, and the nature of foreign trade. I will do this shortly, but first let’s briefly discuss the flows between households and firms in a little more depth.

How Income and

Spending Keep Money Moving

The nature of the circular flow of income and expenditure is such that there is no beginning or end, but it may be convenient to imagine a start point where households provide the factors of production e.g., labor, to firms.

The most obvious example of this, in modern economies like the U.S.A. and U.K., would be people supplying their labor, but it also includes landowners making their land available for lease, and rental income. Similarly capital owners can make their resources available in return for interest payments, and entrepreneurs make themselves available for the pursuit of profit. All these factors reside within households until they are put to use in business.

The expenditure side of things is more straightforward. All people are consumers and all expenditure is done to maximize consumption i.e., to gain the maximum utility from the goods and services that their incomes can afford. This relates to the basic economic problem of scarcity, and how best to satisfy our unlimited wants; attaining the highest level of consumption now and in the future is our ultimate aim in economics.

When incomes fall or spending slows, this circular flow of money weakens, and this is why reductions in consumption often lead to lower output and higher unemployment.

The Five Economic

Sectors in the Circular Flow Diagram

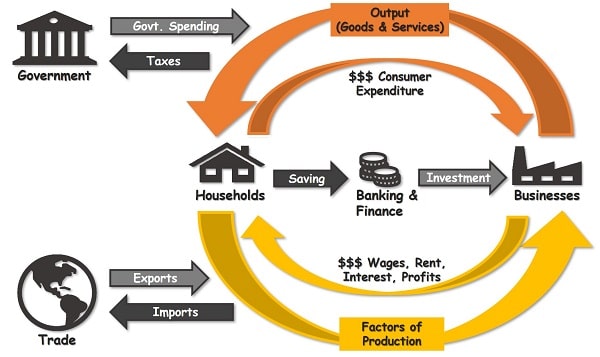

Moving towards a more complete version of the model, there are a total of 5 sectors in the circular flow diagram to explain. The first two, households and firms, are already explained above.

- Households – a household is composed of people, and people play the role of consumers on the one hand, and workers, land owners, capital owners, and entrepreneurs on the other hand.

- Firms – firms are those organizations that bring together, and pay for, the factors of production. These businesses produce the output, i.e. goods and services, that are then sold to consumers.

- Banking & Finance – The financial sector matters because it channels saving into investment and determines how easily money moves between households and firms.

- Government – Government includes local, state and federal institutions. It also includes all government funded institutions e.g., public hospitals, education services, highway maintenance, national defense and so on.

- Foreign Sector – This is the import and export market i.e., the foreign goods and services that domestic consumers purchase from foreign firms, and the domestically produced output that is sold to foreign consumers.

We should be clear at this point that there is often some overlap between these different sectors. Some businesses can work for both the private sector and the government sector, as can the people who make up households.

While these sectors exist in all modern economies, their relative size and behavior differs. In the U.S.A., government and financial sector spending heavily influence the circular flow, whereas in the U.K., services and foreign trade play a larger role in circulating money through households and firms.

There is also some controversy as to whether or not the banking and finance sector should be given special attention, and some of the standard economics textbooks do not do so. Nevertheless, those same textbooks do give a great deal of attention to saving and investment flows, so it pays to give a little extra detail for completeness.

As with the other sectors, there is significant overlap in the banking and finance sector, and a great deal of the activity in this sector is conducted across international borders. In fact, as discussed in my article about Balance of Payments Accounting, international capital flows work to partially or completely offset any trade surplus or deficit resulting from the foreign trade flows of imports and exports (depicted in the diagram below).

Circular Flow of Income: Leakages and Injections Explained

In the real economy, money does not simply circulate endlessly between households and firms. Some flows remove money from domestic spending, while others inject it back in. These are known as leakages and injections.

A complete circular flow model including leakages like saving, taxes and imports, and injections such as investment, government spending and exports — showing how different sectors interact in a real economy.

A complete circular flow model including leakages like saving, taxes and imports, and injections such as investment, government spending and exports — showing how different sectors interact in a real economy.Leakages: Where Money

Leaves the Circular Flow Model

- Taxes – Taxes are a leakage from the circular flow model because they are either directly taken from income, or they are levied on goods and services thereby making them more expensive. As a result, consumer spending i.e., consumption, is reduced.

- Imports – Imports do not reduce consumption directly, and they actually increase total utility since consumers prefer them to the goods & services which they would otherwise have bought. However, once money is paid to foreign firms, it exits the domestic economy and, ceteris paribus, reduces the circular flow in future periods.

- Saving – If consumers choose to save money rather than spend it, business output will go unsold and production will be reduced. This will in turn reduce the demand for the factors of production and thereby, ceteris paribus, reduce income. This is known as the paradox of thrift.

In the U.S.A. and U.K., imports and household saving act as significant leakages, diverting money away from domestic spending and slowing the overall circular flow of income.

Injections: How Money

Re-Enters the Economy

- Government Spending – Government spending is the flip-side of taxes, and increases the size of the circular flow. Spending in the U.S.A. (e.g., infrastructure and social programs) and U.K. (e.g., NHS and public services) serves as an injection, returning money to households and businesses and keeping the economy moving. However, the efficiency of government spending in offsetting reduced private spending is widely debated in economics.

- Exports – Exports are an injection into the domestic circular flow model in the same way that imports are an injection into foreign circular flow models. As alluded to above, imports and exports do not necessarily equal themselves out, and where there are deficits or surpluses then international borrowing, investment, and exchange rate movements settle the difference.

- Investment – Investment is often cited as the flip-side of saving, and in a financial system with full reserve banking and interest rates set by the market this would indeed be the case. However, the real world runs on credit, and credit often funds investment rather than saving. Nevertheless, there is still a link between saving and investment levels. Investment is an injection into the model, and is linked to future economic growth.

Circular Flow Diagram

FAQs

How does the circular

flow diagram in economics change during a recession?

How does the circular flow diagram in economics change during a recession?

During a recession, leakages such as saving and unemployment increase while injections like investment and consumer spending decline. This disrupts the balance of the circular flow, leading to reduced income, lower production, and slower economic circulation. In both the U.S.A. and U.K., cyclical downturns amplify leakages like saving and unemployment, while injections such as government spending and investment may weaken, disrupting the circular flow and reducing production and incomes.

Can the circular flow diagram explain inflationary pressures?

Can the circular flow diagram explain inflationary pressures?

Indirectly, yes. If injections (like investment or government spending) consistently exceed leakages, demand may outpace supply, creating inflation. The model can show how excessive income flows might lead to price increases across the economy.

How do digital platforms and the gig economy fit into the

circular flow diagram?

How do digital platforms and the gig economy fit into the circular flow diagram?

Digital platforms blur traditional sector boundaries. Gig workers often act as both producers and consumers, and platform companies may operate across borders, complicating the model’s depiction of firm-household relationships and foreign sector flows.

What impact do central bank policies have on the circular

flow of income?

What impact do central bank policies have on the circular flow of income?

Monetary policy affects the model via the financial sector. By adjusting interest rates or using quantitative easing, central banks influence savings, investment, and credit availability - thereby modifying injections and leakages in the flow. For example, policies by the Federal Reserve in the U.S. or the Bank of England in the U.K. influence credit availability, interest rates, and investment flows, which in turn affect household and business incomes.

How does the circular flow model apply to developing

economies?

How does the circular flow model apply to developing economies?

In developing economies, informal sectors, low financial access, and limited government capacity can distort or weaken the flows. The model still applies, but must be adapted to account for non-market transactions and subsistence-level activity.

How does the circular flow diagram help explain the multiplier

effect?

How does the circular flow diagram help explain the multiplier effect?

The diagram shows how initial injections (e.g., government spending) circulate multiple times through income and consumption loops, amplifying their total impact on GDP - a foundation of the Keynesian multiplier effect.

What the

Circular Flow Diagram Explains — and What it Doesn't

The circular flow diagram is a simplified way of explaining how money moves through an economy, not a complete description of how real economies function. All economic models are abstractions that serve to highlight some basic features of reality, and this model is no exception.

The details of how the complex interplay of one phenomenon interacts with another is left to more specific models, but for a general overview of how money circulates around the economy, the model presented here is sufficient.

One limitation of the circular flow model relates to the role of banking and financial institutions, which is far more complex than is presented here. The model also fails to illustrate how interest rates, exchange rates, debt, and international capital flows influence the economy. These are major influences on any developed economy, and it is a fair criticism to note how any explanation of them is absent from the model.

Another significant limitation of the circular flow model is that it gives no account for inequality in the economy, all factors are assumed to be homogeneous, and even people are assumed to be the same. In the real-world there is a great deal of inequality, my article about the Gini-Coefficient discusses this in some detail.

Despite the limitations, in applied contexts like the U.S.A. and U.K., the circular flow diagram in economics helps illustrate how policy decisions, consumer behavior, and investment choices determine the circulation of money through households, firms, and governments. By stripping the system down to its core flows, the diagram helps clarify why changes in spending, saving, taxation, or investment can have wider consequences – even if it cannot capture every complexity of the real world.

Source:

Oxford University - Macroeconomics II: The Circular Flow of Income (PDF)

Related Pages:

About the Author

Steve Bain is an economics writer and analyst with a BSc in Economics and experience in regional economic development for UK local government agencies. He explains economic theory and policy through clear, accessible writing informed by both academic training and real-world work.

Read Steve’s full bio

Recent Articles

-

What Happens to House Prices in a Recession?

Jan 11, 26 03:13 AM

What happens to house prices in a recession? Learn how different recessions affect housing, why 2008 was unique, and how policy responses change home values. -

Does Government Spending Cause Inflation?

Jan 10, 26 06:01 AM

Does government spending cause inflation? See how waste, crowding out, and stimulus spending quietly push prices higher over time. -

What Happens to Interest Rates During a Recession

Jan 08, 26 05:31 PM

What happens to interest rates during a recession? Explore why rates often fall, when they don’t, and how inflation, policy, and markets interact. -

Circular Flow Diagram in Economics: How Money Flows

Jan 03, 26 04:57 AM

See how money flows through the economy using the circular flow diagram, and how spending, saving, and policy shape real economic outcomes. -

What Happens to House Prices During Stagflation?

Jan 02, 26 09:39 AM

Discover how house prices and real estate behave during stagflation, with historical examples and key factors shaping the housing market.