- Home

- Economies of Scale

- Economies of Scope

Economies of Scope Explained, with a Graph and Example

The existence, or not, of economies of scope in the production process is an important determinant of which goods/services a firm will need to produce in order to minimize its average costs. The key point to keep in mind is that some goods are related, and that producing them together may lead to synergistic advantages over producing them separately.

The classic example, and the one that I have used in my example below, is that of automobile production. Car manufactures do not build different plants to build different models of car, they produce them at the same plant because it is more cost effective to do so.

There are, of course, limitations on the potential benefits from economies of scope, and there is even the potential for diseconomies of scope if firms make unsound investment decisions. In the sections below, I have given examples of both of these outcomes.

Example of Allocation of Resources for Scope Economies

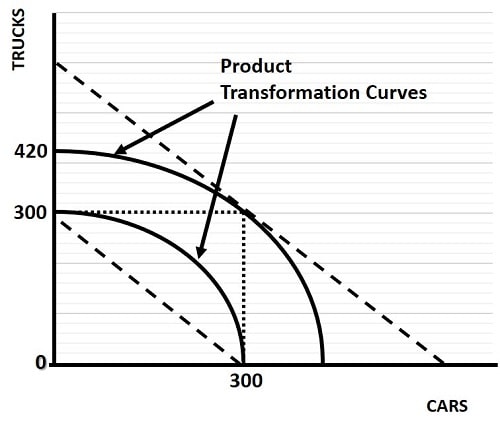

In the Product Transformation Curve graph below, imagine that an entrepreneur is faced with two investment opportunities. He can build a factory that produces 300 cars per month, or a factory that builds 300 trucks per month. For simplicity, let's assume that the market value of the cars and trucks are equal, and that the operating costs of the factories are also equal at each of the plants.

The two options are essentially identical and it doesn't matter which is chosen since both will yield identical returns. Now, let's assume that the entrepreneur chooses to build the truck factory and then later decides that he wants to produce both trucks and cars.

He now faces two additional options. He can either build an entirely new factory with a new workforce on new land etc, in which case his costs of production will double, or he can expand his truck factory in order to be able to produce 300 cars and 300 trucks.

The bowed product transformation curves in the graph illustrate that there are economies of scope from choosing to expand the first factory rather than building an entirely new factory. Similar to the Production Possibilities Curve, the product transformation curve is drawn to indicate all potential combinations of goods that can be produced, but in this case we can adjust the mix of resources used, and we restrict the model to two related products.

The economies of scope arise precisely because cars and trucks are related, and the production technology and techniques are very similar. In the example here, rather than doubling his investment by building an entirely new factory, a much smaller increase in investment will push out the product transformation curve to the point where it brings the production of all 300 trucks and all 300 cars within range. In the example given, production capacity only needs to expand by a factor of 1.4 i.e., 420/300 which is clearly less than double. But why is that?

The reason is because the extra investment needs only to pay for some car-specific technology, the existing workforce already has transferable skills and expertise that can be used for car manufacturing. Much of the existing robotic machinery will be adaptable to producing both cars and trucks, and therefore it makes synergistic business sense for a single factory to produce both.

A small increase in investment in the truck factory will make use of the inherent economies of scope in producing both cars and trucks at the same factory. The inherent similarities in the production process also means that the extra car production facilities could, if needed, be used solely to produce additional trucks. Total truck production capacity increases from 300 to 420 in the example given, and that extra flexibility gives yet another advantage.

Referring again to the graph above, you can see that the concave curvature of the lower product transformation curve reaches out, at the midpoint of the curve, much closer to a production combination point of 300 trucks and 300 cars when compared to the straight dashed line that exists when no economies of scope are present.

All this evidenced in reality where the cost savings inherent in combining the production of related goods at a single facility make the allocation of resources for producing such combinations necessary, assuming the firm wants to survive in a competitive industry. Failure to be competitive would mean that selling prices would need to be higher, and competitor firms would undercut those high prices, thereby driving inefficient non-competitive firms out of business.

Economies of Scope vs Economies of Scale

Economies of scope differ with economies of scale purely on account of the goods/services being analysed. Scope economies are always concerned with potential average cost savings arising from combining the production of multiple related products. Economies of scale, on the other hand, relates only to how long run average costs can be reduced for a given product. For more details on that, have a look at:

Diseconomies of Scope

Think again about the example of a factory that produces cars and trucks, and now consider what would happen if the two options had been trucks and haircuts. Since these two products are entirely unrelated there are no economies of scope to be gained by combining production of these two at a single facility. In this case the product transformation curve would be a straight line.

In fact, if a single firm decided to get into both the car manufacturing and haircut industries, it would suffer diseconomies of scope. Why is that?

The reason is primarily due to the extra complexity, and thus management costs, involved in producing unrelated goods. The larger a firm gets, and the more complex its operations become, the more it will tend to become overly bureaucratic and bogged down by inefficiency and incompetence.

For example, the 1960s and 1970s was a period where many firms were attempting to increase productivity by merging their operations in an attempt to gain from economies of scale. That may well be advisable for related businesses, but when conglomerate businesses started to merge unrelated businesses together they found that any cost savings were outweighed by extra management costs i.e. diseconomies of scope.

We shouldn't be too surprised by this. After all, the ultimate conglomerate is a socialist planned economy where the government organizes all production. The results of such ill-conceived state planning attempts have always been catastrophic, with even simple tasks like producing enough bread to feed the people have been difficult to achieve. Just imagine what would happen if those state planners had tried to do something complex, like produce smartphones. They would look like bricks, cost a fortune, have a 10-year waiting list, and still wouldn't work!

Just to reiterate, economies of scope exist in the production of related goods, not unrelated goods. Scope economies work by reducing the unnecessary duplication of some costs by making better use of existing factors of production.

Sources:

Related Pages:

About the Author

Steve Bain is an economics writer and analyst with a BSc in Economics and experience in regional economic development for UK local government agencies. He explains economic theory and policy through clear, accessible writing informed by both academic training and real-world work.

Read Steve’s full bio

Recent Articles

-

What Happens to House Prices in a Recession?

Jan 11, 26 03:13 AM

What happens to house prices in a recession? Learn how different recessions affect housing, why 2008 was unique, and how policy responses change home values. -

Does Government Spending Cause Inflation?

Jan 10, 26 06:01 AM

Does government spending cause inflation? See how waste, crowding out, and stimulus spending quietly push prices higher over time. -

What Happens to Interest Rates During a Recession

Jan 08, 26 05:31 PM

What happens to interest rates during a recession? Explore why rates often fall, when they don’t, and how inflation, policy, and markets interact. -

Circular Flow Diagram in Economics: How Money Flows

Jan 03, 26 04:57 AM

See how money flows through the economy using the circular flow diagram, and how spending, saving, and policy shape real economic outcomes. -

What Happens to House Prices During Stagflation?

Jan 02, 26 09:39 AM

Discover how house prices and real estate behave during stagflation, with historical examples and key factors shaping the housing market.