- Home

- Supply-side Economics

- Fiscally Responsible

Fiscally Responsible Government (Failures since 1971)

The idea of a fiscally responsible government in the developed western world appears to be somewhat removed from reality, at least in modern times. Soaring debt levels, and budget deficits of a scale that were, until recently, unimaginable outside of a major war, are now embedded in our economies.

There was once a time when fiscally responsible administrations went to great lengths to keep their spending within the confines of their budget constraints i.e. they would be reluctant to spend more than they would raise in taxation, but those days are way behind us.

The reasons for the collapse of prudence in managing the public finances stem from the loss of any external constraint on domestic spending, e.g. like a Gold Standard or a fixed exchange rate system. At the same time, in a bid to gain more popularity at the ballot box, our politicians routinely wage a war of who can promise the most 'free stuff' to an increasingly entitled base of voters.

Unfortunately for all of us, the profligacy with our limited resources has created a hole that threatens to swallow our future standard of living, let alone any vague hope of ongoing growth.

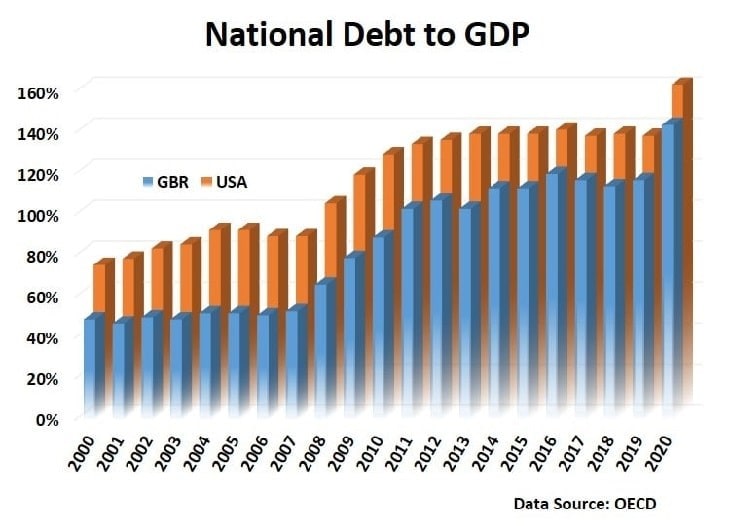

As the graph below illustrates, the national debt burden has been spiraling out of control for over 20 years, and particularly so since the global financial crisis of 2007-08.

The Austrian school of economics would argue that the root cause of this fiscal irresponsibility dates back much further, at least to the collapse of the Bretton Woods system in 1971 when President Richard Nixon suspended the convertibility of the US dollar into gold at a fixed rate of $35 per ounce. The inflation that followed that suspension means that we now count the price of gold ounces in thousands of dollars...

Bretton Woods Collapse

The whole point of the Bretton Woods system, which had been introduced at the end of World War 2, was to provide stability at a time of great upheaval. Great Britain emerged from the war victorious, but financially ruined, and whilst in pre-war years her currency had been used alongside the US dollar as a reserve currency, this was no longer feasible.

The Bretton Woods agreement established the US dollar of the sole reserve currency for participating economies, and international trade was conducted in terms of dollars. The idea was that the dollar would maintain a fixed value in terms of gold at $35 per ounce. The other countries participating in the system then had to maintain the value of their own currencies in terms of the dollar, so the system was effectively one of fixed exchange rates backed by gold.

The problem was that the US (as with other countries) faced ever increasing political demands that required funds. The welfare state, healthcare, the Vietnam War, the Cold War and so on all meant that a fiscally responsible government would need to continually raise taxes to keep up with these expenses. But, as we all know, tax rises are not popular with voters.

The response, from successive US administrations, was to expand the money supply in order to try and generate more economic growth, but this led to inflation. As inflation grows, the value of the currency declines, and in 1971 the the system could no longer support the dollar at a price of $35 per ounce.

This marked the end of the Bretton Woods system, and with it the need for fiscal responsibility was significantly reduced.

Now, the point here is not to suggest that a return to this system, or something similar to it, would be the correct path to follow at the current time. It is rather to illustrate that the loss of any external constraint on government spending will tend to lessen the likelihood of fiscally responsible spending programs.

Causes of Fiscal Irresponsibility in Modern Times

Whilst the collapse of the Bretton Woods system in 1971 may have heralded a new era of fiscally irresponsible government spending, we still need to resolve the question of why our governments are so complacent in their attitudes towards ever growing debt levels. After all, governments of a hundred years ago were very serious about achieving, and maintaining, a balanced budget.

The original fundamental change in attitude dates back to the inception of Keynesian economic policies i.e., policy ideas introduced by the British economist John Maynard Keynes. The big change with this approach, following the hardship of the Great Depression, was that governments could, and should, act to keep their economies growing along a stable path.

Furthermore, they should maintain this stable path by actually increasing spending during economic slowdowns, in order to boost aggregate demand. This, of course, would entail running up large debts in order to pay for that extra spending at a time when tax-receipts would be declining because of the slowdown.

The point that our modern governments seem to have overlooked is that Keynes also intended that, during economic boom periods, the debts that were allowed to grow during the slowdown should be paid off so that there would be a balanced budget in the long-run.

Historical experience has proven that whilst it is all too easy to run up debts during the slowdowns, it is far less easy to repay them during the good times. As Milton Friedman famously quipped: "Nothing is so permanent as a temporary government program". The problem is that once these programs are initiated, it becomes politically costly to stop them, and governments place the importance of votes above all else.

Three Specific Problems that affect Government Spending

I'll close this article with some specific issues that have derailed fiscally responsible spending in the west for many years, and threaten to continue doing so for the foreseeable future:

De-Industrialization

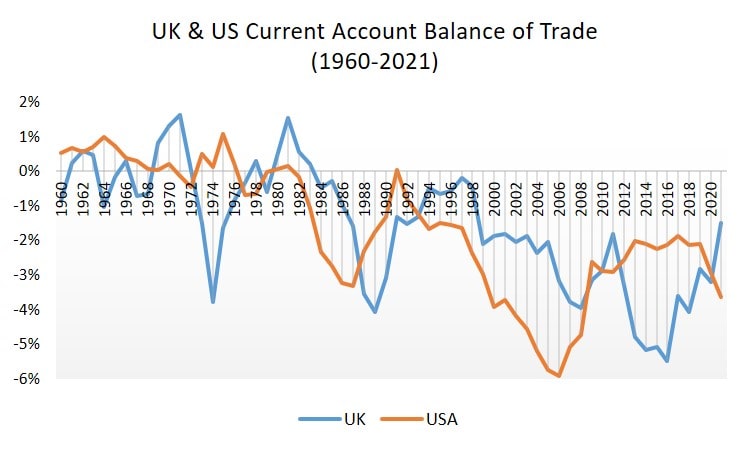

The globalist agenda has allowed the 'offshoring' of a huge proportion of our manufacturing industries. Many have either relocated into Asia where cheap labor costs are abundant, or they have gone bankrupt in the face of competition from those cheap Asian producers.

One of the effects of this is to provide very cheap imported goods for domestic consumers and, whilst that is no bad thing, it has contributed to keeping overall inflation levels low whilst other domestically produced goods and services have become much more expensive.

Were it not for the falling prices of the imported goods, inflation would have risen significantly and thereby forced our governments to slow the economy down by cutting its spending and raising interest rates.

What has actually happened is that, as more and more goods are imported from overseas, huge numbers of our jobs have been lost, and many more people that were once taxpayers have become dependent on state benefits - meaning that government spending has increased whilst tax receipts have fallen.

The gap in funding has been covered by increased borrowing, in large part from the foreign manufacturers who have replaced our domestic manufacturers. The result is that our national debt has sky-rocketed. Fiscally responsible governments would never have allowed this, but governments fueled by an insatiable globalist agenda have welcomed it.

Spiraling Education Costs

With the loss of traditional industries like mining, ship-building, manufacturing, and so on, the skills necessary to gain well-paid employment in the growth industries usually require at least an undergraduate degree from a reputable university. Those universities have competed to gain a growing share of the student body by offering world-class facilities of all types, which has massively increased the cost of getting an education.

Worse still, the quality of the actual tuition has been of dubious benefit to the student.

Add to this the fact that there appears to be a political agenda to push as large a proportion of young people into universities as is feasibly possible... presumably so that they don't show up on the official unemployment statistics.

Getting young people to university may be a fine thing, but doing so at a cost that will cripple them financially for the rest of their working lives makes little sense, especially since the actual demand for graduate employees has not kept pace with the supply. Many graduates, who have been encouraged to rack up huge personal debts, have had to settle for entry-level jobs after graduating - jobs that require only a minimal level of basic skills.

An Aging Population

For many decades the birth rate in the US, the UK, and most other developed economies has been declining. At the same time there has been some increases in human longevity, even whilst a huge and growing proportion of our population has become more and more metabolically unhealthy.

Obesity levels are sky-high and growing, with diabetes and pre-diabetes growing in tandem.

The end result of this process is a much larger proportion of the population that is either retired or too ill to work. This has had obvious consequences for the government coffers, which are now stretched to breaking point.

At the same time, welcome improvements to the body of scientific knowledge in terms of creating new treatments and medicines, have created extremely difficult choices for the government in deciding which healthcare services can be provided via general taxation, and which cannot be provided.

Related to this is the problem of state pension provisions. The retirement age in some western countries has been pushed back in recent years, but the ratio of people in work to those who have retired has decreased, and it looks set to continue doing so.

A fiscally responsible government will need to face up to this issue at some point, and difficult choices will need to be made that will not be popular with voters. Time will tell whether or not this will be done in a timely manner, but the omens are not good.

Sources:

- Michael Bordo - Demise of the Bretton Woods System

- OECD - National Debt

- OECD - Current Account Balance

Related Pages:

- Discretionary Fiscal Policy

- The Economics of Decline

- Inflation, what is it, and why is it bad?

- Cyclical Unemployment

- The Long Term Debt Cycle

- Supply-Side Economics

- The Full Reserve Banking System

About the Author

Steve Bain is an economics writer and analyst with a BSc in Economics and experience in regional economic development for UK local government agencies. He explains economic theory and policy through clear, accessible writing informed by both academic training and real-world work.

Read Steve’s full bio

Recent Articles

-

What Happens to House Prices in a Recession?

Jan 11, 26 03:13 AM

What happens to house prices in a recession? Learn how different recessions affect housing, why 2008 was unique, and how policy responses change home values. -

Does Government Spending Cause Inflation?

Jan 10, 26 06:01 AM

Does government spending cause inflation? See how waste, crowding out, and stimulus spending quietly push prices higher over time. -

What Happens to Interest Rates During a Recession

Jan 08, 26 05:31 PM

What happens to interest rates during a recession? Explore why rates often fall, when they don’t, and how inflation, policy, and markets interact. -

Circular Flow Diagram in Economics: How Money Flows

Jan 03, 26 04:57 AM

See how money flows through the economy using the circular flow diagram, and how spending, saving, and policy shape real economic outcomes. -

What Happens to House Prices During Stagflation?

Jan 02, 26 09:39 AM

Discover how house prices and real estate behave during stagflation, with historical examples and key factors shaping the housing market.