- Home

- Business Cycle

- Legislative Lag

Legislative Lag in Economic Policy, Explained (with Example)

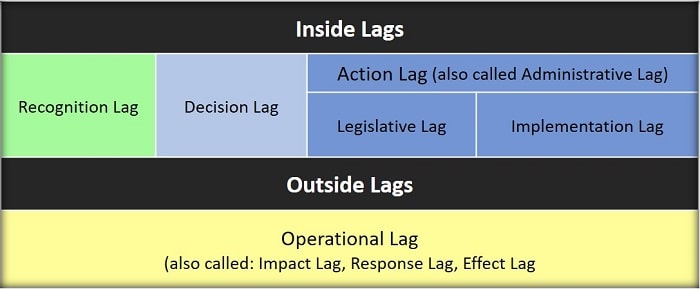

Legislative lag is the second component part of what economists call the action lag (or administrative lag) of stabilization policy. It specifically refers to the time period that occurs in between a decision being agreed and then getting that decision implemented.

Naturally, this particular type of policy lag almost always relates only to fiscal policy and hardly ever to monetary policy (for an exception see the example below). That's because there is no legislation that needs to be passed by the 'upper house' (e.g., the United States Senate, the UK House of Lords, etc.) in order to enact monetary policy - the Federal Reserve has full authority to approve changes to monetary policy in the US, via an agreement of the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC).

Discretionary fiscal policy cannot be approved so quickly, and may require many months of drafting, followed by much debate, with proposed amendments that may require more debate and so on. In this article I will discuss the theory behind legislative lag, and how effective it is in practice as a means of managing economic shocks.

The Policy Lag Chart & Legislative Component

The policy lag chart below shows the various types of lag that occur with stabilization policy, and legislative lag is illustrated by the first component part of the action lag. I should point out here that there are certain situations where all these policy lags may sum up to zero time elapsed, or even a negative time lag; that might be the case if a deviation of the economy away from its long term growth path was completely foreseen many months in advance. That would allow sufficient time for policymakers to fully prepare ahead of time.

In reality, being able to fully prepare an economic policy response ahead of time is highly unlikely because economic forecasting is inherently unpredictable with any degree of accuracy (hence the term economic shock), but there are occasions where policymakers can prepare.

For example, if a country knows that it will soon be at war then it will be able to predict some of the economic consequences of that war, and make provisions to accommodate those consequences ahead of time.

In the majority of cases an economic shock, by definition, is not foreseen and all of the policy lags illustrated in the chart will come with some real delay. The legislative lag is in some ways the most difficult to predict because there may be partisan political factors at play. This might be the case if a ruling party in government does not control a majority in the senate/parliament, and the opposition party/parties are opposed to any particular fiscal policy legislation.

Long periods of debate, amendments, compromises, promises, and so on will likely ensue, causing long delays in these processes (see the example below for details).

For details on the other sorts of lags, see my articles at:

Discretionary Fiscal Policy Formulation

The time taken to pass a fiscal policy bill through the legislature is, as already noted above, heavily influenced by the partisan nature of politics in many countries. It is also true that some legislative processes naturally take longer due to extra complications that need more time for debate and consideration.

The legislators in the US Congress or UK Parliament, as with other democratic countries, have a duty to carefully inspect every aspect of any proposed bills because the unintended consequences of any new laws can have seriously detrimental consequences for an economy. Due diligence by the legislative body must be done in order to mitigate this possibility wherever possible.

Countercyclical fiscal policy is no exception to this rule, even though there may be extra pressure to pass bills in a timely fashion due to the natural urgency of the situation. Politics does nevertheless play a big part in the legislative process, and it is no accident that expansionary fiscal policy has tended to be approved by the legislators somewhat faster than contractionary fiscal policy. The popularity with voters of the former compared to the unpopularity of the latter clearly has an influence here.

Legislative Lag Example

Arguably the most important legislative lag example in modern times occurred after the 2007-08 financial crisis. Basel 3, or the Third Basel Accord, was not a typical stabilization policy aimed at tackling a current deviation from the long-run economic growth path, nor was it a fiscal policy at all (it's more closely related to monetary policy), but I'd argue that it still qualifies.

Basel 3 was a direct legislative response to what was recognized as being a major destabilizing force on the domestic and global economy, i.e. fractional reserve banking in the fiat system.

The idea behind the new accord was that the banking sector had been far too loose with money creation in the run up to the financial crisis and that new legislation was required to regulate the ability (or incentives) of the banks to create too much money at times when the economy is in danger of overheating.

The new measures that were introduced aimed to increase liquidity and improve the reserve ratios held by the banks, with a new 'capital adequacy' requirement that is intended to ensure that banks hold a sufficiently large amount of their reserves in highly liquid assets, such as government bonds and other financial assets, that can quickly be converted into cash in times of economic stress. This would help protect the financial system from insolvency and reduce the likelihood that the government would need to step in with future bailout programs at the taxpayer's expense.

Now, given that a number of years have passed since the accord was agreed, we might ask ourselves what the results have been.

- Firstly, there was a long legislative lag of over 3 years between the start of the financial crisis and the accord finally being agreed in November 2010.

- Secondly, the accord was only intended to be implemented from 2013 - 2015, but had to continually be extended due to ongoing weakness in the financial system.

- Thirdly, the effect of the accord in encouraging banks to purchase financial assets has been to create the most severe economic bubble in financial assets that the modern world has ever seen, and in 2022 it looks set to burst with devastating consequences for the global economy!

Such is the incompetence of state legislative bodies.

Stabilization Policy Problems

Stabilization policy problems are many and varied and do not only apply the legislative lag issues described on this page. For details of the other sorts of problems I'd encourage you to read up on the other articles I've linked to on this page. The underlying issue nearly always comes down to the very difficult nature of hands-on economic management, and government incompetence with such things.

The economy is too unpredictable for the government to manage reliably, and its credibility is compromised by its desire to push policies that will win votes rather than deliver true value. We see this time and time again, and if anyone has any doubt then you have merely to ask yourself why the government has run up such huge debts when it could have paid for its policies via an increase in tax rather than an increase in borrowing.

Such incompetence, or negligence, has brought us to the brink of a major economic collapse. Inflation is sky high and getting worse, wage rates will rise fast enough to keep up with rising prices, and lenders are reluctant to lend us more money without significantly higher interest rates - rates that we cannot afford to pay. The only answer to this is to keep printing more money to fund the government budget deficit, and that will only cause more inflation and an eventual collapse of the economy.

Far from stabilizing the economy, the government has, over many decades and particularly since 2008, manufactured the economic weaknesses in the west that now seriously threaten our standards of living. Well, at least we can still manufacture something!

Related Pages:

About the Author

Steve Bain is an economics writer and analyst with a BSc in Economics and experience in regional economic development for UK local government agencies. He explains economic theory and policy through clear, accessible writing informed by both academic training and real-world work.

Read Steve’s full bio

Recent Articles

-

What Happens to House Prices in a Recession?

Jan 11, 26 03:13 AM

What happens to house prices in a recession? Learn how different recessions affect housing, why 2008 was unique, and how policy responses change home values. -

Does Government Spending Cause Inflation?

Jan 10, 26 06:01 AM

Does government spending cause inflation? See how waste, crowding out, and stimulus spending quietly push prices higher over time. -

What Happens to Interest Rates During a Recession

Jan 08, 26 05:31 PM

What happens to interest rates during a recession? Explore why rates often fall, when they don’t, and how inflation, policy, and markets interact. -

Circular Flow Diagram in Economics: How Money Flows

Jan 03, 26 04:57 AM

See how money flows through the economy using the circular flow diagram, and how spending, saving, and policy shape real economic outcomes. -

What Happens to House Prices During Stagflation?

Jan 02, 26 09:39 AM

Discover how house prices and real estate behave during stagflation, with historical examples and key factors shaping the housing market.