- Home

- Business Cycle

- Recognition Lag

Recognition Lag in Economic Policy, Explained (with Example)

Recognition lag in economics refers to a situation in which some sort of significant disturbance to the long run stable economic growth path has occurred, but has yet to be recognized by policymakers and statisticians.

There are cases where a disturbance, or economic shock, is foreseen before it takes place and, obviously, in such cases there is no recognition lag because the process of changing economic policy to accommodate that shock can begin immediately.

However, in most cases, an economic shock will come totally unforeseen (as implied by the term 'shock'). In these cases it may well take a period of months before the official statistics pick up on any impact to the economy, and so there will be significant time lost before any corrective action can take place.

Types of Lags in the Economy

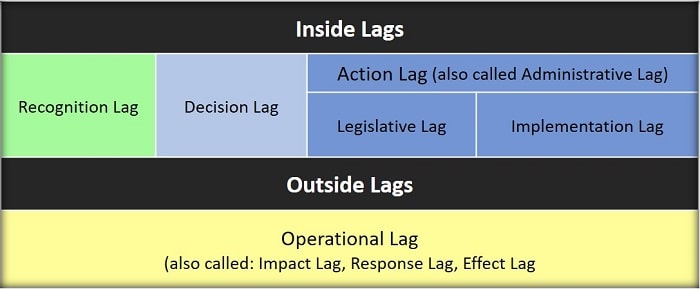

As the chart below illustrates, economists have broken down the various types of lags in economic policy formulation (known as impact lags), and its eventual impact on the economy (known as outside lags).

The recognition lag is the first of these, followed by the decision lag, legislative lag, and the implementation lag. After this, the time taken for a new policy to have an effect is usually called the operational lag or the response lag, but I have heard other names used on occasion, so it pays to be aware of the possible confusion caused by all these different names.

I have written about these other lags in my articles at:

Recognition Lag Example

The textbook example of this, at least for Keynesian economists, occurs when business confidence changes for some reason. Business confidence, as well as consumer confidence, is highly unpredictable and impossible to forecast with any degree of accuracy. So, when it changes significantly it is usually unforeseen and it results in a significant fall in business investment levels.

Investment is regarded as being the most volatile component of aggregate demand by Keynesians, which is why it is assumed to be the most common cause of the boom & recession cycle in the economy.

Particular examples of a sizable recognition lag occurred in the build up to:

- The Great Recession - this was initiated by the 2008 financial crisis. The boom years prior to this crisis had been thought to be sustainable because growth ran concurrent with low inflation. In truth, this was a time of massive overheating, with vast twin deficits opening up on the trade account and the government's tax & spend budget.

- The 1997 Asian Financial - initiated by the collapse of the dot.com bubble. The years prior to this had also been thought to be years of sustainable growth, but again it turned out that our economic policy masters were operating on flawed economic models.

In both of the cases above, standard practice would be to regard the recognition lag as applying to the period between an economic disturbance occurring, and the statistics on the economy recording that disturbance. However, it is open to interpretation when the real disturbances occurred, and in both cases above it clearly preceded the actual deterioration of the economic growth path. Rather, it occurred when growth started to exceed its sustainable path with bubble markets developing, and those bubbles always start to develop years before they eventually burst.

Monetary Policy & Discretionary Fiscal Policy Lags

Unlike the other types of stabilization policy lags, recognition lag is identical for both monetary policy and fiscal policy actions. Intuitively this is obvious, because neither of these countercyclical interventions in the economy will be implemented until a cyclical deviation from the long run growth path has been recognized.

Typically, according to the research that has been conducted, the duration of the recognition lag is estimated to be around 3 months. However, I'd encourage the reader to keep my earlier comments in mind, because there is no objective process of identifying when economic growth has deviated from its trend level, and without an objective start date any estimate of recognition lag duration is rendered subjective and open to debate.

There is also some evidence of differences relating to whether or not the economy is thought to be entering a recession or a boom, with slower recognition of booms meaning that government expansionary fiscal policy (or Federal Reserve monetary policy) tends to be slower off the blocks than contractionary fiscal policy.

Recognition of Boom Periods in the Economy

Whilst appropriate policy may be delayed somewhat following the failure to recognize a downturn in the economy, that delay may be much longer when it comes to recognizing that economic growth has accelerated beyond its sustainable long run growth path.

Politicians have in-built incentives to capitalize on the good times because they know that their popularity depends in large part on presiding over a thriving economy with low levels of unemployment. This can easily lead to cognitive bias, whereby information can be innocently (or deliberately) misinterpreted in a favorable light.

Hindsight is perfect, but it is difficult to believe that the economic boom years in the United States and other western countries in the early 2000's could have been innocently misinterpreted. It would be extremely difficult to reconcile the rapid inflation of house prices, right up to 2007, with an oversight by our political elites. If this was an innocent oversight, or miscalculation, then we have to acknowledge that the recognition lag can last for several years even in the face of cold hard data that records unprecedented housing and real estate booms!

Neither fiscal policy nor monetary policy was used to cool down the economy in the years running up to the 2007-2008 financial crisis, so it does seem that there is some sort of recognition problem at play when the economy is growing too quickly.

Conclusion

There are reasonable grounds to be a little skeptical of any research that suggests how long it takes for the necessary economic data to be collected and analyzed before any discernible deviation of the economy from its long run growth path can be confirmed. Political forces may well interfere with this determination, but in any case it certainly takes at least a few months before anything can be determined.

There are, as stated at the outset, cases whereby there is a zero lag with regard to recognizing a disturbance to the economy. For example, the lockdowns imposed by the government in response to the Covid-19 pandemic came with an anticipation of severe economic disruption, and we could even argue in this example that the recognition lag was negative. Any foreseen disruptions are predicted ahead of time, with positive lags only relevant starting with what decision to take regarding suitable mitigating action.

Nothing has been written in this article about the desirability of countercyclical fiscal policy (or monetary policy), and it is simply assumed that such action is a positive thing. This, however, is not at all necessarily the case. There are many occasions in which it is best for the government to do nothing at all, and let market forces do their thing because a self-correction may be least disruptive. That will be discussed more in my article about operational lag.

Sources:

Related Pages:

About the Author

Steve Bain is an economics writer and analyst with a BSc in Economics and experience in regional economic development for UK local government agencies. He explains economic theory and policy through clear, accessible writing informed by both academic training and real-world work.

Read Steve’s full bio

Recent Articles

-

What Happens to House Prices in a Recession?

Jan 11, 26 03:13 AM

What happens to house prices in a recession? Learn how different recessions affect housing, why 2008 was unique, and how policy responses change home values. -

Does Government Spending Cause Inflation?

Jan 10, 26 06:01 AM

Does government spending cause inflation? See how waste, crowding out, and stimulus spending quietly push prices higher over time. -

What Happens to Interest Rates During a Recession

Jan 08, 26 05:31 PM

What happens to interest rates during a recession? Explore why rates often fall, when they don’t, and how inflation, policy, and markets interact. -

Circular Flow Diagram in Economics: How Money Flows

Jan 03, 26 04:57 AM

See how money flows through the economy using the circular flow diagram, and how spending, saving, and policy shape real economic outcomes. -

What Happens to House Prices During Stagflation?

Jan 02, 26 09:39 AM

Discover how house prices and real estate behave during stagflation, with historical examples and key factors shaping the housing market.