- Home

- Monetary Policy

- Permanent Income Hypothesis

Permanent Income Hypothesis Explained (U.S. Evidence)

The Permanent Income Hypothesis presents a more advanced model of consumer spending than that of the basic Keynesian Consumption Function, and it raises yet more questions about the efficacy of short-term demand management policies as tools of macroeconomic stabilization.

The hypothesis as it stands today is actually a sort of amalgam of two similar theories:

- The Permanent Income Theory (by Milton Friedman)

- The Life-cycle Hypothesis (by Franco Modigliani)

Friedman was a leading opponent of Keynesian economics whilst Modigliani was an advocate, but both of these theories came to a similar conclusion i.e. that increases in transitory income do not lead to significant increases in consumption, only permanent of life-time income increases will do that.

If you have studied Keynes you will probably be aware of the 'fundamental psychological law' that sits at the foundation of his theory about consumption i.e. that as income rises so does consumption albeit at a lesser rate.

Well, it turns out that whilst this is correct in the long-run, the insignificant relationship between income and spending in the short-run presents problems for Keynesian economists since their policy recommendations are based on short-term dynamics.

The implication of the Permanent Income Hypothesis is that the Marginal Propensity to Consume (MPC) is actually very small in the short-term and that, consequently, the Keynesian Multiplier is also likely to be small.

US Disposable Income and Consumer Spending

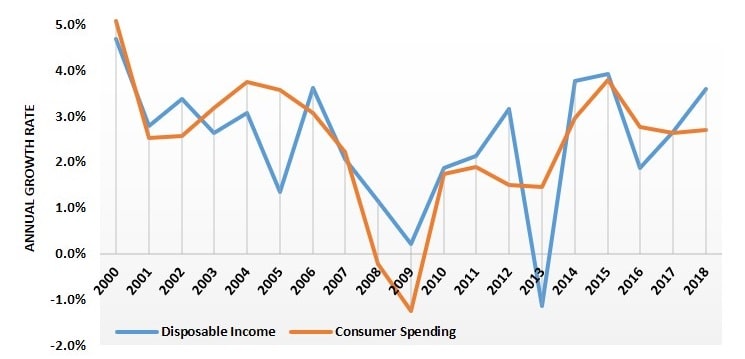

In the graph below, the predictions of the permanent income hypothesis are confirmed by the divergences in the two lines from 2000 to 2018 (the figures are provided by the OECD - see the link at the end of the page).

Correlation between US disposable income and consumer spending, from 2000 to 2018.

Correlation between US disposable income and consumer spending, from 2000 to 2018.The pattern of consumer spending is shown by the orange line, and it diverges significantly from the blue disposable income line on three occasions over the period:

- In the run up to the 2007-08 financial meltdown consumer spending growth exceeded that of disposable income. This was probably due to high expectations of capital gains from investment in the housing market which was booming at that time.

- From 2008 to 2013 the 'great recession' period saw consumer spending grow much more slowly than disposable income, and even shrank during the worst hit years as many homeowners lost huge amounts of equity in their homes.

- In 2013 there was a sharp fall in transitory disposable income due to unusual circumstances. However, by this time the great recession was over, and consumer confidence had returned meaning that spending levels were not impacted in any significant way.

The first two examples caused changes in anticipated permanent income levels, and so consumer spending reacted strongly. The 2013 fall in disposable income was seen as being very much a one-time only event (see the link to the CNN Business report at the bottom of the page) and therefore did little to reduce expected permanent income levels, which meant consumer spending continued unabated.

I think that the key take-home point here is that consumption will vary depending on current economic circumstances because those circumstances can affect people's expected permanent income levels. One-off tax cuts, or a handout of stimulus checks, are far less likely to cause changes to future expected earnings, and therefore the permanent income hypothesis would predict that they will not cause spending to increase significantly.

I would add a caveat to the stimulus check example in that, to the extent that the pandemic lockdowns have kept consumers away from the shopping malls, bars, restaurants and so on for so long that they are going stir-crazy, an easing of those lockdowns may well cause a splurge of consumer spending in celebration of their new-found freedoms.

I may be wrong on this because short-term economic forecasting is highly unpredictable by its nature, and that unpredictability is precisely the problem that undermines any active Keynesian demand management policy from the government. Stimulus checks will more likely be used to reduce credit card debts and personal loans rather than fuel extra spending, but there are too many other factors at play to have any real idea of what will happen post-lockdown.

Robert E. Hall has formulated this problem in his 'Random-Walk Model' which is presented as:

C(t+1) = C(t) + ϵ

In words this simply means consumption in the next time-period equals consumption in this time-period plus a random error (see the link at the bottom of the page for details).

Consumption, Growth & Inequality Problems

Some practical problems arise with the permanent income hypothesis in the real world because it is not always possible for consumers to even out their consumption in times when their incomes are low compared to their expected lifetime average earnings.

This is particularly problematic for people who are either at university or in the early stages of the career when the earnings are low. There are, of course, loans available that can be used to bolster current consumption, but the amounts available are unlikely to be sufficient to fill the gap. In these cases we say that consumers face liquidity constraints.

There may also be some reticence on the part of people to borrow large amounts of money if there is any uncertainty about their future earnings growth potential. Furthermore, people may be happy enough to spend less at times in their lives when their responsibilities are lower, and when their friends are also earning lower amounts i.e. students. Conversely, later on in life they may feel more pressure to spend if they are supporting a family, or if their friends and neighbors are spending higher amounts. These, and other, inequality factors distort the predictions from the model.

Finally, the permanent income hypothesis implies that at some point older consumers should start to spend their savings since it is of no use to them after they die. In reality, even when older people have no dependents to pass their wealth on to, they usually prefer to live off the income that their wealth generates, rather than eat into that wealth.

Of course, if we knew the precise date at which we will die then things might be different, but what if we spend all of our wealth and then live twenty years longer than anticipated? Clearly some caution needs to be exercised here.

Conclusion

Whilst the Permanent Income Hypothesis certainly casts extra doubts over the ability of any policy-maker to effectively manage the economy in the short-term, it remains to be seen whether its key observation will always be correct in any given situation.

The problem with all of these theories is that they are based on empirical evidence, or observation of past behavior. This type of research may give great confidence in its results when it is applied to the natural sciences, but people are not particles, and observing how they may have behaved in the past does not give much certainty about how they will behave in future because there are always unique factors at play that the research fails to take into account.

What the Permanent Income Hypothesis does do is add yet more evidence (if any more were needed) that Keynesian demand management policies are an exercise in futility. What it cannot do (at least in the opinion of the Austrian school of economics to which I subscribe) is provide an alternative framework for managing the economy at a macro level. Such things are best left to the free-market in all but exceptional circumstances.

Data Sources:

- OECD - Disposable Income & Household Spending

- CNN Business - The 2013 Income Drop

- Robert E. Hall - Random Walk Theory of Consumption

Related Pages:

- The Keynesian Consumption Function

- The Keynesian Multiplier

- Quantity Theory of Money

- Velocity of Money

- Money Multiplier

About the Author

Steve Bain is an economics writer and analyst with a BSc in Economics and experience in regional economic development for UK local government agencies. He explains economic theory and policy through clear, accessible writing informed by both academic training and real-world work.

Read Steve’s full bio

Recent Articles

-

What Happens to House Prices in a Recession?

Jan 11, 26 03:13 AM

What happens to house prices in a recession? Learn how different recessions affect housing, why 2008 was unique, and how policy responses change home values. -

Does Government Spending Cause Inflation?

Jan 10, 26 06:01 AM

Does government spending cause inflation? See how waste, crowding out, and stimulus spending quietly push prices higher over time. -

What Happens to Interest Rates During a Recession

Jan 08, 26 05:31 PM

What happens to interest rates during a recession? Explore why rates often fall, when they don’t, and how inflation, policy, and markets interact. -

Circular Flow Diagram in Economics: How Money Flows

Jan 03, 26 04:57 AM

See how money flows through the economy using the circular flow diagram, and how spending, saving, and policy shape real economic outcomes. -

What Happens to House Prices During Stagflation?

Jan 02, 26 09:39 AM

Discover how house prices and real estate behave during stagflation, with historical examples and key factors shaping the housing market.