- Home

- Production Possibilities Curve

- Isocost Line

Isocost Line in Economics, Explained (Graph & Formula)

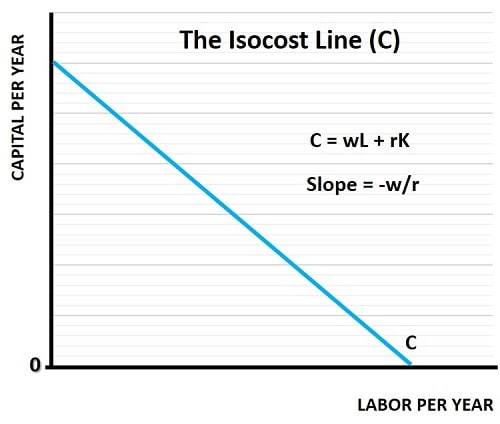

The Isocost line, sometimes called the isocost curve, is a long run concept in economics that can be graphed to show all possible combinations of labor and capital for a given total cost. These costs are assumed to be the total costs of production for simplicity’s sake but, in reality, there are also land and enterprise costs to consider.

The simplification does not affect the point of the isocost line, which is to provide a reasonable explanation of how firms allocate resources and input costs in order to maximize profit. As such, the isocost line is an important component of ‘the theory of the firm’ in economics.

Unless otherwise stated, it is standard practice to assume that the firm under inspection is a small firm operating in a competitive market, and that it has no market power to influence its input costs i.e., the wage rate or interest rate costs that it pays.

The Isocost

Line Formula

Given the simplifications stated above, we can state that the total cost that a firm will have to pay to produce output is given by the sum of:

- The amount of labor it employs multiplied by the wage rate.

- The amount of capital it uses multiplied by the rental cost it pays.

Typically, we write this as C = wL + rK, and to derive the isocost line formula we need to rewrite this in the form of a linear equation i.e., a simple straight-line formula. Some basic algebra allows to transpose to:

K = C/r – (w/r)L

This is the Iscocost Line Formula.

As I mentioned at the beginning, the term isocost curve is sometimes used, suggesting that something other than a straight line should apply. Sometimes this is an arbitrary point and can be ignored or used interchangeably with the term isocost line, but if the firm has market-power then it will be able to influence either the wage rates or rental costs that it pays. In that case the isocost line would not be linear, it would bend into an actual curve.

I mention this for clarity but, in this model, we always assume (unless otherwise stated) that the firm operates in a competitive market with no market-power to affect input prices.

Isocost Line Graph

Referring back to the linear equation above, K = C/r – (w/r)L, it should be clear that the slope of the isocost line is given by -(w/r). Since it is a linear equation i.e., a straight line, the slope of the isocost line is constant and equal to the wage rate divided by the rental cost, w/r, and since w/r is preceded by the negative sign we know that it is downward sloping, as illustrated in the graph above.

The Isoquant

and Isocost Line

The Isoquant is a similar concept to the isocost line, but opposite in the sense that it holds the total amount of output produced by a firm as fixed, while allowing the amounts of labor and capital used to vary.

By utilizing both of these concepts together, we can derive an efficient production point for an optimized level of output with total costs minimized. For an example of this, see my article about the Cost Minimization.

Conclusion

& Final Thoughts

The Isocost line is a simple microeconomics concept that assumes competitive markets for input costs. By itself it doesn’t have much use, but when combined with other concepts it helps to build up a model of efficient capital and labor combinations for the production of output at minimum cost.

The cost of capital is given as the rental cost of capital, but in broader macroeconomic analysis the rental cost of capital is usually described as an interest rate, because the cost of borrowing money is given by the interest rate that is paid. Capital costs are usually paid for via a loan of some sort, or by using retained profits which means giving up the interest that could have been earned by investing in an alternative asset instead of capital.

The slope of the isocost curve depends on the relative costs of capital and labor and, while these can fluctuate, they do not do so because of any market power on the part of the firm under scrutiny. When costs do change, it is because market dynamics have changed, and that will then affect the slope of the isocost line.

Related Pages:

- User Cost of Capital

- Marginal Rate of Technical Substitution MRTS

- Costs of Production

- The Production Possibilities Curve

About the Author

Steve Bain is an economics writer and analyst with a BSc in Economics and experience in regional economic development for UK local government agencies. He explains economic theory and policy through clear, accessible writing informed by both academic training and real-world work.

Read Steve’s full bio

Recent Articles

-

What Happens to House Prices in a Recession?

Jan 11, 26 03:13 AM

What happens to house prices in a recession? Learn how different recessions affect housing, why 2008 was unique, and how policy responses change home values. -

Does Government Spending Cause Inflation?

Jan 10, 26 06:01 AM

Does government spending cause inflation? See how waste, crowding out, and stimulus spending quietly push prices higher over time. -

What Happens to Interest Rates During a Recession

Jan 08, 26 05:31 PM

What happens to interest rates during a recession? Explore why rates often fall, when they don’t, and how inflation, policy, and markets interact. -

Circular Flow Diagram in Economics: How Money Flows

Jan 03, 26 04:57 AM

See how money flows through the economy using the circular flow diagram, and how spending, saving, and policy shape real economic outcomes. -

What Happens to House Prices During Stagflation?

Jan 02, 26 09:39 AM

Discover how house prices and real estate behave during stagflation, with historical examples and key factors shaping the housing market.