- Home

- Aggregate Demand

- Autonomous Consumption

Autonomous Consumption (Graph & Real Examples)

Autonomous consumption refers to the portion of an individual's spending that is not influenced by changes in income. It is a key determinant of economic output because it directly affects consumer spending, the largest component of a country's GDP.

Macroeconomic models tend to skip over any explanation of what determines autonomous consumption, but by delving deeper into the factors that underlie it we can gain valuable insights into how individual spending habits shape the overall economic landscape.

The standard treatment of autonomous consumption is to regard it as the minimum level of spending that individuals engage in regardless of their income levels i.e., it represents the basic necessities and essential goods and services that individuals require to maintain a certain standard of living.

These expenses are typically non-discretionary and include items such as food, housing, utilities, and healthcare. Autonomous consumption is influenced by factors such as cultural norms, personal preferences, and the cost of living.

That being the case, autonomous consumption is not static, and it can vary significantly between individuals and across different regions or countries. Factors such as income inequality, cultural differences, and government policies can all influence the level of autonomous consumption within a society.

Autonomous Consumption

vs. Induced Consumption

To fully understand the concept of autonomous consumption, it is important to distinguish it from induced consumption. While autonomous consumption refers to the minimum level of spending that individuals engage in regardless of income changes, induced consumption is the portion of spending that varies with changes in income.

Induced consumption is influenced by changes in income levels and represents the additional spending individuals engage in when their income increases. For example, if an individual receives a salary increase, they may choose to spend a portion of that additional income on discretionary items such as vacations, luxury goods, or entertainment. This additional spending contributes to increased consumer demand and stimulates economic output.

My article about the consumption function explains the Keynesian ideas that bring autonomous and induced consumption together into a unified theory of consumption, and its impact on economic output. However, as already indicated, that Keynesian model skips over any real discussion of the factors that drive autonomous consumption.

Autonomous Consumption Graph

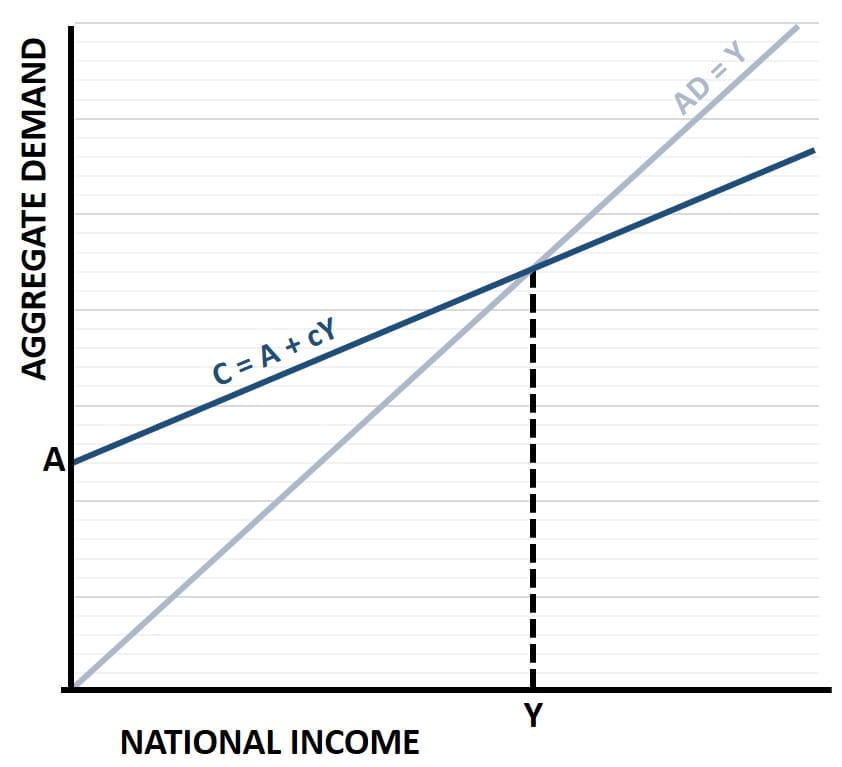

A graph with an upward sloping consumption function that intersects the aggregate demand axis at a positive level (A), indicating an amount of consumption that is autonomous of national income.

A graph with an upward sloping consumption function that intersects the aggregate demand axis at a positive level (A), indicating an amount of consumption that is autonomous of national income.In the graph above, autonomous consumption is indicated by the level of consumption that occurs when national income is zero. Zero national income is, of course, impossible, but we assume for simplicity that the entire consumption function C = A + cY is lifted by this constant amount of autonomous consumption at all other non-zero levels of national income.

As can be seen, point A marks the level of autonomous consumption that occurs in this instance.

Factors influencing

individual spending habits

Individual spending habits are influenced by a multitude of factors, ranging from psychological factors to external economic conditions. One of the key psychological factors that influence spending habits is consumer confidence.

When individuals feel optimistic about the future and have a positive outlook on their personal finances, they are more likely to engage in higher levels of spending. On the other hand, during periods of economic uncertainty or financial instability, individuals tend to reduce their spending and focus on essential items.

Cultural factors also influence individual spending habits. Cultural norms, values, and traditions can shape the way individuals prioritize their spending. For example, in some cultures, saving for the future may be highly valued, leading individuals to allocate a significant portion of their income towards savings and investments. In contrast, in cultures that emphasize immediate gratification, individuals may prioritize spending on immediate desires rather than saving for the future.

The point here is that countries with thrifty citizens are better equipped to maintain their spending habits in times of unemployment and low/no income. This helps to avoid any serious recession by smoothing out spending so that the economic boom bust cycle is reduced in magnitude. In other words, countries with thrifty citizens tend to enjoy greater economic stability. This would imply that the consumption function should be less steep in thrifty countries i.e., that the marginal propensity to save is high and, conversely, that the marginal propensity to consume is lower.

Via a similar line of reasoning, the level of autonomous consumption within a society might also indicate the overall economic well-being of its citizens. This is because higher levels of autonomous spending might indicate that there have probably been higher rates of saving in previous periods, and that that must have come from high levels of national income.

Interestingly, this association has been shown to be weak, and there is a lack of evidence that saving rates increase substantially as a country gets richer from one period to the next. It is true, however, that in any given period individual people do tend to save more of their disposable income as they get richer. This is consistent with the permanent income hypothesis.

The role of government in influencing autonomous consumption

The government plays a crucial role in influencing autonomous consumption through various policies and regulations. One way to achieve this is through social safety net programs to support individuals with limited (or zero) financial resources. Programs such as unemployment benefits, welfare assistance, and healthcare subsidies can provide individuals with a basic level of support, ensuring that they can meet their essential needs even during periods of financial instability.

By providing a safety net, the government can help maintain a certain level of autonomous consumption that contributes to economic stability. However, the right balance needs to be found because social safety nets that are too generous are known to discourage work i.e., the so-called benefits trap.

A special case arises in times of national emergencies, such as a major war or the Covid 19 lockdowns. In such cases income may be reduced drastically, and the government will likely take action to provide stimulus checks in order to maintain autonomous consumption of basic necessities. The danger here is that this kind of spending quickly leads to sky-high national debt, and it creates inflationary pressure in the economy due to too many monetary units chasing too few consumer goods & services.

Real-World

Examples: Autonomous Consumption in the U.S. and U.K.

Autonomous consumption is not just a theoretical construct, it shows up clearly in real economies, especially during periods of economic stress when incomes fall but essential spending does not.

United

States: Essential Spending During Income Shocks

In the U.S., household consumption of necessities such as food, housing, healthcare, and utilities tends to remain relatively stable even when employment or real incomes decline.

This pattern was visible during the 2020 recession. While overall economic output and employment fell sharply, spending on core necessities declined far less than discretionary categories such as travel, entertainment, and dining out. Many households maintained baseline consumption by drawing on savings, increasing credit usage, or relying on government transfers.

The Federal Reserve’s Survey of Household Economics and Decision making (SHED) documents how households smooth consumption during income disruptions, prioritizing rent, groceries, and utilities even when income becomes uncertain or temporarily disappears. This behavior closely matches the idea of autonomous consumption i.e., spending that continues independently of current income.

In practical terms, this explains why consumer spending in the U.S. often proves more resilient than expected during downturns, even when real wages stagnate or unemployment rises.

United

Kingdom: Cost-of-Living Pressures and Forced Spending

In the U.K., autonomous consumption is especially visible during periods of high inflation and rising living costs.

Since 2021, households have faced sustained increases in the cost of essentials such as energy, food, and housing. Even as real disposable incomes were squeezed, spending on these categories remained elevated because they are difficult or impossible to cut below a minimum level.

Analysis shows that many households responded by reducing discretionary spending, running down savings, or increasing debt rather than reduce essential consumption. This reflects a baseline level of autonomous spending driven by necessity rather than income growth.

In this context, autonomous consumption helps explain why inflation can persist in essential goods even when economic growth weakens: demand for necessities remains relatively inelastic, especially in the short run.

Why These

Examples Matter

These U.S. and U.K. cases illustrate why autonomous consumption plays a central role in:

- Recession dynamics

- Inflation persistence in essential goods

- The effectiveness (and limits) of fiscal support

- Household financial fragility during economic stress

Understanding autonomous consumption helps explain why consumer spending does not fall one-for-one with income, and why economic downturns often play out differently than simple income-based models would predict.

FAQs

Can autonomous

consumption change over time?

Can autonomous

consumption change over time?

Yes. Autonomous consumption is not fixed, it evolves with living standards, social norms, and institutional structures. For example, the minimum level of spending required for housing, healthcare, or digital connectivity today is higher than it was decades ago. As essential goods and services expand, the baseline level of consumption households consider non-negotiable also rises, increasing autonomous consumption over time.

How does autonomous

spending differ across income groups?

How does autonomous

spending differ across income groups?

Lower-income households typically have a higher share of consumption that is autonomous because a larger portion of their spending goes toward necessities. Higher-income households can reduce discretionary spending more easily during income shocks, whereas lower-income households are forced to maintain essential consumption even when income falls, often by borrowing or dissaving.

Does autonomous

consumption explain why recessions are not always demand collapses?

Does autonomous

consumption explain why recessions are not always demand collapses?

Partly, yes. Because a portion of consumer spending is autonomous, total demand does not fall as sharply as income during many downturns. Essential spending continues even when confidence weakens, which helps stabilize aggregate demand and prevents economic contractions from spiraling as quickly as simple income-based models might suggest.

What role does

household debt play in sustaining autonomous consumption?

What role does

household debt play in sustaining autonomous consumption?

Household debt allows consumption to remain above current income levels in the short term. Credit cards, overdrafts, and personal loans are commonly used to finance essential spending during income disruptions. While this supports autonomous consumption temporarily, it can increase financial vulnerability if income does not recover.

Is autonomous

consumption affected by interest rates?

Is autonomous

consumption affected by interest rates?

Indirectly. Higher interest rates increase the cost of borrowing, making it harder for households to finance essential spending through credit. Over time, this can constrain autonomous spending, especially for households that rely on short-term borrowing to smooth income fluctuations. However, in the short run, necessity-driven spending often persists despite higher rates.

Why is autonomous

consumption important for understanding long-term economic stress?

Why is autonomous

consumption important for understanding long-term economic stress?

Because it highlights structural pressures rather than short-term behavior. Rising housing costs, healthcare expenses, and energy prices increase the baseline cost of living, pushing autonomous consumption higher. Over time, this reduces economic resilience and makes households more sensitive to shocks, even during periods of apparent economic growth.

Conclusion

Autonomous consumption plays a crucial role in supporting economic output in times of recession, and it helps to smooth out the severity of the boom bust business cycle. The government can also help to smooth out this cycle via providing the right balance of social safety net provisions.

Policies that aim to encourage saving a greater proportion of disposable income, rather than encouraging more and more spending on current consumption, can also help to build provisions for autonomous spending in times of reduced income. Unfortunately, this is not standard practice among western government policymakers. Current consumption seems always to be prioritized, and while that may increase living standards in the short-term, it leaves our economies vulnerable to economic downturns.

Related Pages:

About the Author

Steve Bain is an economics writer and analyst with a BSc in Economics and experience in regional economic development for UK local government agencies. He explains economic theory and policy through clear, accessible writing informed by both academic training and real-world work.

Read Steve’s full bio

Recent Articles

-

What Happens to House Prices in a Recession?

Jan 11, 26 03:13 AM

What happens to house prices in a recession? Learn how different recessions affect housing, why 2008 was unique, and how policy responses change home values. -

Does Government Spending Cause Inflation?

Jan 10, 26 06:01 AM

Does government spending cause inflation? See how waste, crowding out, and stimulus spending quietly push prices higher over time. -

What Happens to Interest Rates During a Recession

Jan 08, 26 05:31 PM

What happens to interest rates during a recession? Explore why rates often fall, when they don’t, and how inflation, policy, and markets interact. -

Circular Flow Diagram in Economics: How Money Flows

Jan 03, 26 04:57 AM

See how money flows through the economy using the circular flow diagram, and how spending, saving, and policy shape real economic outcomes. -

What Happens to House Prices During Stagflation?

Jan 02, 26 09:39 AM

Discover how house prices and real estate behave during stagflation, with historical examples and key factors shaping the housing market.