- Home

- Market Failure

- Marginal External Cost

Marginal External Cost Explained (Graph & Examples)

Marginal external cost is a term associated with negative externalities involved in a trade, i.e. bad effects suffered by third parties as a result of a trade between a buyer and a seller of a good or service.

There is, of course, a huge incidence of such situations in the real world that occur every day, but the vast majority of them are of only minor impact and are not significant enough to warrant any corrective action.

When the marginal external cost of production/consumption is significant, then it must be taken into account when making production/consumption decisions if society is to achieve optimal outcomes.

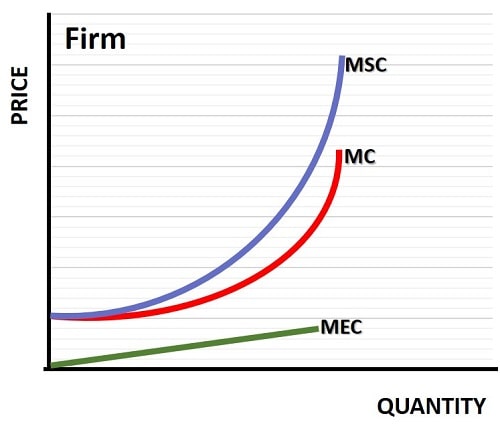

The marginal external cost curve (MEC) forms a component of the overall marginal social cost curve (MSC) as illustrated in the graph below, and by the equation:

MSC = MEC + MPC.

The only potential for confusion here is that MPC (marginal private cost) tends to be the preferred term when looking into externalities, rather than the more standard term MC (marginal cost).

The standard MC is basically the same concept, and since most industries are not considered to have significant externalities, there is usually no need to distinguish between private and external costs.

Marginal External Cost Formula

A simple rearrangement (transposition) of the equation above gives us the result that:

MEC = MSC - MPC

This is the marginal external cost formula.

We may or may not know how to calculate marginal external cost, with any degree of precision, depending on the nature of problem, but on the graph the MSC curve is raised higher than the MC curve (or MPC curve if you prefer) by the height of the MEC curve at each point.

The graph used above is labelled as applying to an individual firm, but the same analysis applies for the entire industry. The degree of competitiveness in any given industry does not affect the curves or their relationship to one another.

The level of competition would, of course, affect price and output decisions, and by extension the amount of external cost produced, but that can be mitigated by the right combination of corrective taxation imposed on the industry by government.

Slope of the Marginal External Cost Curve

For simplicity we assume that marginal external cost increases at a constant rate, and so the curve is actually a straight line, but this may or may not reflect reality depending upon each case.

Some situations may see increasingly large external costs produced with each extra unit of output, in which case the MEC curve would slope upwards at an increasingly steep rate.

In other situations it may be that external costs hit a peak at some critical output level, and incur no further costs from additional output. Each case is unique.

Marginal External Cost Examples

The obvious example of significant marginal external cost being imposed on third parties is that of pollution. Pollution may be created as part of the production process, or from the waste created by consumption e.g. throwaway plastic containers.

Problems of this nature can be very difficult to correct due to the global impact that they have. Carbon emissions pollute the atmosphere, waste plastic pollutes the oceans, but any specific country where such pollution is created has an incentive to ignore it since much of the costs fall upon other countries.

Obviously, if the costs fell entirely upon the country where the pollution is created then there would be sufficient marginal external cost created to motivate corrective action, but this is not so when the costs are dispersed globally.

In these circumstances, global initiatives to promote environmentally friendly measures may be adopted, as well as potential restrictive trade policies, such as tariffs, may be used to tackle marginal external cost problems.

More Real-World Examples of Marginal External Cost

- Air Pollution from Factories - A manufacturing plant may produce goods at a low private cost, but its smokestack emissions can harm nearby residents’ health and damage crops. External costs may include hospital visits, reduced agricultural yields, and environmental cleanup costs.

- Road Traffic Congestion - When drivers enter a busy highway, they consider their own fuel and time costs, but they rarely account for the extra delays they cause other drivers. External costs include lost time and increased fuel usage for all other road users.

- Noise from Airports - Air travel benefits passengers and the economy, but takeoffs and landings can generate noise pollution that disrupts nearby neighborhoods. External costs are stress, reduced property values, and sleep disturbances for residents.

- Overfishing in Shared Waters - Fishing companies may catch as much as possible to maximize profit, but each extra boat reduces fish stocks for everyone. External costs include depletion of fish populations, ecosystem imbalance, and reduced future catches.

- Plastic Waste and Marine Pollution - Disposable plastic items are cheap for producers and consumers, but once discarded, they can harm marine life and require costly cleanup efforts. External costs are ocean cleanup programs, loss of tourism revenue, and harm to fisheries.

Policy Tools for Reducing Marginal External Costs

When markets fail to account for marginal external costs, they tend to produce more of a good or service than is socially optimal. Economists and policymakers use several tools to “internalize” these costs, meaning they make decision-makers bear the full marginal social cost (MSC) of their actions.

Corrective Taxes - These are taxes set equal to the marginal external cost at the socially optimal quantity. Their purpose is to raise the private cost (MPC) so it matches the social cost (MSC).

Pigouvian Subsidies - Named after economist Arthur Pigou, While taxes deal with negative externalities, subsidies can encourage behaviors that reduce harm. Their purpose is to make it cheaper to switch to less damaging alternatives.

Tradable Permits (Cap-and-Trade) - Governments set an overall cap on harmful activities (e.g., total emissions allowed) and issue permits. Companies can trade these permits in a market. Their purpose is to limit total damage while allowing flexibility in who reduces the activity.

Regulations and Standards - Rather than using prices, regulators can directly limit harmful activities through rules. The purpose is to set clear boundaries when immediate or guaranteed reductions are needed.

Property Rights and the Coase Theorem - If property rights are clearly defined and transaction costs are low, affected parties can negotiate to internalize the externality without government intervention. The purpose is to let market participants solve the problem themselves.

FAQs

What is marginal external cost in economics?

What is marginal external cost in economics?

Marginal external cost (MEC) is the extra cost imposed on society by producing one additional unit of a good or service, excluding the private costs paid by the producer. It is calculated as the difference between marginal social cost (MSC) and marginal private cost i.e. standard marginal cost (MC).

How does marginal external cost differ from marginal external benefit?

How does marginal external cost differ from marginal external benefit?

Marginal external cost measures harm to third parties from an extra unit of output, while marginal external benefit measures positive spillovers. Both are components of marginal social cost or benefit analysis.

Can marginal external costs be negative?

Can marginal external costs be negative?

In economics, a “negative” marginal external cost is actually a marginal external benefit. For example, planting trees may lower nearby cooling costs and improve air quality.

How do economists calculate marginal external costs in practice?

How do economists calculate marginal external costs in practice?

They may use damage cost valuation, willingness-to-pay surveys, hedonic pricing (e.g., property value impacts), or avoided cost methods to estimate the harm.

What role do discount rates play in calculating external costs?

What role do discount rates play in calculating external costs?

Discount rates adjust the present value of future damages, which is important when costs, such as climate change impacts, occur far in the future.

Can technology reduce marginal external costs without government intervention?

Can technology reduce marginal external costs without government intervention?

Yes. Innovations like cleaner production methods, electric vehicles, or noise-reducing aircraft engines can lower MECs by reducing harm per unit of output.

Conclusion

Marginal external cost helps us to understand how individual decisions can create broader social harms that markets often fail to address on their own. By identifying and measuring these costs, economists and policymakers can design targeted solutions, such as taxes, permits, or regulations, that align private incentives with the public good.

Related Pages:

- Marginal Social Cost

- Marginal Cost of Abatement

- Socially Optimal Quantity of Output

- Marginal External Benefit

- Externalities in Economics

- Types of Market Failure

About the Author

Steve Bain is an economics writer and analyst with a BSc in Economics and experience in regional economic development for UK local government agencies. He explains economic theory and policy through clear, accessible writing informed by both academic training and real-world work.

Read Steve’s full bio

Recent Articles

-

What Happens to House Prices in a Recession?

Jan 11, 26 03:13 AM

What happens to house prices in a recession? Learn how different recessions affect housing, why 2008 was unique, and how policy responses change home values. -

Does Government Spending Cause Inflation?

Jan 10, 26 06:01 AM

Does government spending cause inflation? See how waste, crowding out, and stimulus spending quietly push prices higher over time. -

What Happens to Interest Rates During a Recession

Jan 08, 26 05:31 PM

What happens to interest rates during a recession? Explore why rates often fall, when they don’t, and how inflation, policy, and markets interact. -

Circular Flow Diagram in Economics: How Money Flows

Jan 03, 26 04:57 AM

See how money flows through the economy using the circular flow diagram, and how spending, saving, and policy shape real economic outcomes. -

What Happens to House Prices During Stagflation?

Jan 02, 26 09:39 AM

Discover how house prices and real estate behave during stagflation, with historical examples and key factors shaping the housing market.