The NAIRU Explained

The NAIRU, which stands for the 'Non-Accelerating Inflation Rate of Unemployment', is a modern Phillips Curve theory of inflation and unemployment, which holds that policy-makers have a simple tradeoff decision to make between reducing unemployment and accepting more inflation, or vice-versa.

Since this supposed tradeoff started to fail in the 1970s, it should be no surprise to learn that the NAIRU was developed at that time as an explanation of what could cause a situation of both increasing unemployment and increasing inflation in the economy.

The crucial breakthrough came with the theory of inflation expectations, and how it is only inflation over and above that which is already expected that can maintain levels of employment above a certain point. If pursued by government policy this would, of course, fail utterly.

Constantly rising inflation very quickly turns into hyperinflation, and a complete collapse of the financial monetary system, so the lesson given by the NAIRU model is that expansionary economic demand-management is often both inflationary and futile.

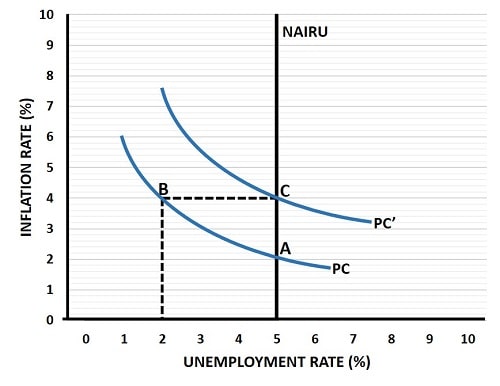

The workings of the NAIRU model are best explained with the visual aid of a graph.

The NAIRU level is represented by the vertical line. In this example it is set equal to a 5% unemployment rate irrespective of the inflation rate. The 5% figure should not be taken literally here, because in reality it can vary significantly at different times according to circumstances.

The NAIRU versus The Natural Rate

The NAIRU is not designed to explain all forms of actual unemployment, it is not really a long-run model at all, and should not be confused with the Natural Rate of Unemployment. Its main purpose is to show the short/medium run effects of a demand-management stimulus package on cyclical unemployment. That being the case, when other types of unemployment are higher or lower (primarily structural unemployment) then the vertical NAIRU will move to a new rate accordingly.

However, real-world estimates of the NAIRU do put it close to about 5% most of the time.

On the graph, imagine that as a starting point our fictional economy starts at point A with a natural rate of unemployment of about 5% and a non-accelerating inflation rate of about 2%. In the real world this would actually be a very good position to be at, with a low inflation rate and close to most estimates of the long-run natural rate of unemployment.

However, let's assume that it's election year and the incumbent government wants to increase its popularity with voters by getting the actual unemployment rate even lower. So, for opportunistic reasons the government decides to pursue an expansionary economic demand-management policy, and to this end it starts increasing its spending on some key social projects. This creates an injection of funds into the economy and an increase in aggregate demand.

Increasing aggregate demand has two effects.

Firstly, the extra funds that enter the economy start to push prices higher as predicted by the quantity theory of money i.e. with more money circulating in the economy and no corresponding increase in the amount of output, firms will be able to charge higher prices. As prices increase, profits also increase, which now kick-starts firms into increasing production of goods and services.

Secondly, as output levels increase, an unemployment gap emerges which firms will fill by recruiting extra workers to help with production.

As the NAIRU graph illustrates, with both rising prices (inflation) and falling unemployment, our economy starts to move along the Phillips curve (PC) from point A to point B where it settles on an unemployment rate of about 2%, which is well below the sustainable rate.

Inflation at point B has risen from 2% to 4%. If the government has timed its opportunist expansion policy well, an election will soon follow with an appreciative electorate rewarding them with more votes for their performance in reducing the unemployment rate.

However, this is not the end of the story.

This is where the key breakthrough in the NAIRU theory starts to take effect, because in the next wage negotiation period the workers in the economy will notice that their wages are being eroded by the higher inflation rate, and they will demand higher wages to compensate them for their loss of purchasing power. They argue that their employers have increased their profits because they are selling more output at a higher price, but their wages are not rising in line with those prices.

With such a low unemployment rate at point B, workers have plenty of negotiating power in the labor market, and they will soon get their pay increases agreed. As this process plays out, the excess profits that businesses were earning will be eroded by the higher wage growth, and as this happens output will shrink back to its original level, with employment/unemployment also returning to their original levels. Eventually, the economy reaches point C on the graph, the Phillips curve has shifted to a higher tradeoff level, from PC to PC', and output has returned to its original sustainable level.

Unfortunately, and this is the key point, inflation does not return to its original level. It has permanently risen to around 4% because 'inflationary expectations' have increased.

The Expectations Augmented Phillips Curve

In economics, the term 'Adaptive Expectations' refers to the process by which economic agents react to recent experiences in forming their future expectations. As far as inflation is concerned, this means that whatever it was in the previous period (usually a year), it will have a big influence on what we expect it to be in the next period.

If economic agents expect a high level of inflation in the next period, then this becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy. Many producers in the economy need to arrange contracts for raw materials a long time in advance of actually receiving those raw materials, and no supplier of those raw materials is going to agree to a price now that doesn't reflect his expectation of what his payment will be worth when he receives it in the next period.

So, if inflation was high in the previous period, the supplier will want to build in a premium to compensate for an expectation of high inflation in the next period. Some producers may be able to negotiate some contracts depending on their market power, but unless the supplier was being paid too much in the first place then it will not be possible to avoid higher costs going forward.

However, whilst the producer will have to pay the supplier more to cover the extra anticipated inflation, he will respond by increasing the price of his own product in the next period to cover his own extra costs. So consumers end up paying a higher price in the next period just because inflationary expectations are now built into the system.

The upshot of this is that there is not one Phillips curve but many, each one with a specific rate of expected inflation built into it. The trade-off between higher unemployment or higher inflation (and vice-versa) still applies in the short-run, but each short-run curve is an 'Expectations Augmented Phillips Curve'. In the NAIRU graph above, the PC and PC' curves are both augmented for the different levels of expected inflation in the two different time periods.

The Non-Accelerating Inflation Rate of Unemployment - Additional Notes

As with all models of the economy, the Non-Accelerating Inflation Rate of Unemployment concept and the Expectations Augmented Phillips Curve framework is a simplification of real life. To use the model effectively you need to use the age-old 'ceteris paribus' approach i.e. you need to hold all other variables constant.

There are many other variables in the real world that will affect both the NAIRU and the tradeoff between inflation and unemployment e.g. productivity growth (which increases labor demand and lowers unemployment irrespective of inflation), but we hold them constant to allow meaningful inspection of the specific variables under analysis.

Returning to point A in the graph above, you should note that maintaining the economy at that stable point, with stable inflation and unemployment, requires the Federal Reserve Bank to set monetary policy just right to keep the money-supply growing at the same rate that the economy grows, so as to keep everything in balance.

Furthermore, some level of positive growth is needed to maintain a low unemployment level because of advances in technology i.e. better technology allows the same level of economic output to be produced with a smaller number of employees, so maintaining the same number of employees requires some growth. This is known as Okun's Law, and whilst the relationship between growth and employment hasn't always held in the short-run, it is quite stable in the long-run.

Natural, Theoretical & Practical Criticisms

Theoretical criticisms of the NAIRU are harder to make than practical criticisms. The most pertinent practical criticism relates to the very significant measurement difficulties involved in estimating where all these curves are at any given point in time. We know that the NAIRU can change over time, so estimating its true value at any specific time is troublesome, which also makes policy recommendations very difficult.

We also know that the Expectations Augmented Phillips Curve is constantly moving around, adding to the difficulty of using the NAIRU model in any sort of active demand-management policy.

The main implication of the NAIRU is that active demand-management should not be a policy tool in most cases, and that it only boosts output in the economy temporarily at best, and just causes extra inflation in the end. New Keynesian economists challenge this position because they tend to prefer to push for a lower unemployment rate in most circumstances.

Some critics, mainly on the political left, are philosophically opposed to the notion that there is a level of unemployment below which governments should not seek to go. They deride those economists who support the NAIRU theory as somehow working to stop some people from getting jobs, but this type of economic perspective is nonsense and should not be taken seriously.

To criticize the NAIRU is fine, but to suppose that some people use it to fulfill their evil desires of keeping other people out of work is just foolish. I wouldn't usually make such an obvious point, but it seems that the world in which we live these days has no shortage of such naysayers.

Any reasonable theoretical criticisms of the NAIRU are best made on the grounds that, perhaps, inflation expectations and their influence on future levels of actual inflation might be incorrect.

For a scholarly article on the NAIRU, have a read of: The NAIRU In Theory & Practice

Rational versus Adaptive Expectations

The 'Rational Expectations Theory' is a recent development in economics that was put forward by the neoclassical schools of economics. The idea is that with repeated short-term demand-management policies that produce no real lasting benefits on the labor market, economic agents will eventually start to anticipate the full effects of a short-term stimulus and immediately react to it in such a way that the long-run effects are immediately reached.

This would make even short-term benefits from such stimulus policies impossible and, as is demonstrated in the NAIRU graph above, this would mean that an expansion starting from point A, would skip point B, and go straight to point C.

Most economists are critical of the rational expectations theory, and at the current time there is little evidence of stimulus packages being completely ineffective in the short-run.

The principle of 'Adaptive Expectations' is most closely intertwined with the NAIRU model in economics. Empirical evidence over the past few decades has lent a great deal of weight to the principle, with a strong correlation between the theory and real life outcomes.

The late great Irving Fisher was the first economist to put forward the idea of adaptive expectations in his book 'The Purchasing Power of Money'. Irving Fisher is a favorite of mine, and I'll be deferring to his judgement again on this site, especially with regard to the optimal banking system.

There is, however, some disagreement about how adaptive expectations are formed. In simple models economic agents are assumed to set their expectation of next year's inflation as being equal to this year's inflation. In more sophisticated models the trend over a few years is considered i.e. they look at last year's inflation, but they also consider whether there has been a pattern of increasing or decreasing inflation in the years preceding.

Ultimately, whatever the correct formula for estimating how expectations are adapted, the theory itself seems quite sound at the current time. Of course, the soundness of a model depends more on how accurately its predictions match future outcomes, and just because historically the empirical evidence has been supportive of the Expectations Augmented Phillips Curve & NAIRU, there is no guarantee of what will happen in the economy in future.

Data sources:

Related Pages:

- What is Inflation, and why is it bad?

- Sticky Wages & Prices

- The Phillips Curve

- The Sacrifice Ratio

- The Quantity Theory of Money

- Does Quantitative Easing Cause Inflation?

- Neutrality of Money

- The Beveridge Curve

- Creeping Inflation

- Galloping Inflation

- Cyclical Unemployment

About the Author

Steve Bain is an economics writer and analyst with a BSc in Economics and experience in regional economic development for UK local government agencies. He explains economic theory and policy through clear, accessible writing informed by both academic training and real-world work.

Read Steve’s full bio

Recent Articles

-

What Happens to House Prices in a Recession?

Jan 11, 26 03:13 AM

What happens to house prices in a recession? Learn how different recessions affect housing, why 2008 was unique, and how policy responses change home values. -

Does Government Spending Cause Inflation?

Jan 10, 26 06:01 AM

Does government spending cause inflation? See how waste, crowding out, and stimulus spending quietly push prices higher over time. -

What Happens to Interest Rates During a Recession

Jan 08, 26 05:31 PM

What happens to interest rates during a recession? Explore why rates often fall, when they don’t, and how inflation, policy, and markets interact. -

Circular Flow Diagram in Economics: How Money Flows

Jan 03, 26 04:57 AM

See how money flows through the economy using the circular flow diagram, and how spending, saving, and policy shape real economic outcomes. -

What Happens to House Prices During Stagflation?

Jan 02, 26 09:39 AM

Discover how house prices and real estate behave during stagflation, with historical examples and key factors shaping the housing market.