What Happens to Interest Rates During a Recession

What happens to interest rates during a recession is often treated as a simple question with a simple answer: they go down. In practice, interest rates usually fall during economic downturns, but not always, and not in the same way across the financial system.

The direction, speed, and magnitude of interest rate changes depend on the causes of the recession, inflation dynamics, central bank constraints, and how markets interpret policy actions.

Recessions are periods of economic contraction marked by falling demand, weaker investment, and rising uncertainty. Central banks typically respond by lowering short-term policy rates to reduce borrowing costs and support economic activity. At the same time, market interest rates reflect expectations about inflation, government debt, financial risk, and future growth.

This means that while some rates may fall quickly, others may remain elevated or even rise, particularly during inflation-driven or supply-constrained downturns.

Clearly, a full appreciation of what happens to interest rates during a recession requires looking beyond headline rate cuts and examining how monetary policy, market expectations, and economic incentives interact.

How Interest

Rates Work

To understand what happens to interest rates during a recession, it’s important to first understand what people mean when they talk about “interest rates.” There isn’t just one rate. Instead, there is a layered system of rates that interact with each other, driven by both central bank policy and market forces.

When headlines say that interest rates are rising or falling, they are usually referring to a central bank’s policy rate, but households and businesses typically borrow and save at market rates that respond imperfectly to that policy signal.

At the top of this system are central bank policy rates, such as the Federal Reserve’s federal funds rate (FFR) in the United States or the Bank of England’s bank rate in the UK. These rates influence very short-term borrowing between banks and serve as a benchmark for the broader financial system.

Central banks adjust these rates to influence economic conditions, aiming to manage inflation, employment, and financial stability. During a recession, changes in the policy rate are meant to alter incentives by making borrowing cheaper or more expensive.

Below the policy rate are market interest rates, which are shaped by expectations, risk, and supply and demand for credit. These include:

- Mortgage interest rates

- Corporate loan rates

- Government bond yields

- Savings account and CD rates

Market rates respond to policy changes, but they are not controlled directly by central banks. Long-term interest rates, in particular, depend heavily on expectations about future inflation, economic growth, and government borrowing. This is why mortgage rates can sometimes rise even when central banks are cutting short-term rates, or why savings rates may fall faster than loan rates during an economic downturn.

The key point is that interest rates are both a policy tool and a market signal. Central banks can push short-term rates up or down, but the broader structure of interest rates reflects how investors, lenders, and borrowers interpret economic conditions.

During a recession, these signals often shift rapidly as risk increases, demand weakens, and expectations about future growth change. Understanding this distinction helps explain why interest rates do not always move in a simple or uniform way when the economy contracts.

Do Interest Rates Go Down in a Recession?

Do interest rates go down in a recession? In most modern recessions, they usually do, but this outcome is the result of both policy decisions and market behavior rather than an automatic economic law. Recessions are typically marked by falling demand, weaker investment, and rising cyclical unemployment.

As spending slows, inflationary pressures often ease, giving central banks more room to reduce policy rates in an attempt to support economic activity.

- Central banks lower short-term interest rates during a recession to influence incentives across the economy. Cheaper credit is intended to encourage borrowing, reduce debt servicing costs, and prevent a collapse in investment.

- At the same time, financial markets often reinforce this downward pressure. As uncertainty rises, investors tend to move capital into safer assets such as government bonds, increasing demand and pushing yields lower.

Together, these forces usually result in declining interest rates, particularly at the short end of the yield curve.

However, while it is common for interest rates to fall during a recession, the pattern is neither uniform nor guaranteed. Different types of interest rates respond differently, and the broader economic context matters.

Short-term policy rates are the easiest for central banks to influence, while long-term rates depend more heavily on expectations about inflation, national debt levels, and future growth.

When

Interest Rates Go Up

The circumstances in which interest rates can rise during a recession, or remain elevated despite a weakening economy, tend to occur when inflation remains high, or when the downturn is driven by supply-side shocks rather than falling demand.

In these cases, central banks may be reluctant to cut rates aggressively, as doing so could worsen inflation or undermine confidence in the currency. As a result, policy rates may stay higher for longer, even as economic activity contracts.

Market interest rates can also move higher if investors demand greater compensation for risk. During periods of financial stress, lenders may raise rates on loans and mortgages to offset higher default risk, even if central bank policy rates are stable or falling.

Long-term bond yields can increase if investors expect persistent inflation, rising government debt, or future rate hikes.

These scenarios help explain why asking what happens to interest rates during a recession does not always produce a simple answer. The direction of rates depends not just on the recession itself, but on its underlying causes and the constraints facing policymakers and markets.

Historical

Case Studies and Why Outcomes Differ

Looking at past recessions helps clarify what happens to interest rates during a recession, but it also shows why outcomes can differ dramatically depending on the underlying economic conditions.

While many downturns are associated with falling rates, history provides several clear examples where rates either remained high or rose, particularly when inflation expectations were unstable or policy credibility was weak.

U.S. Interest Rates During Recessions, 1979–1984

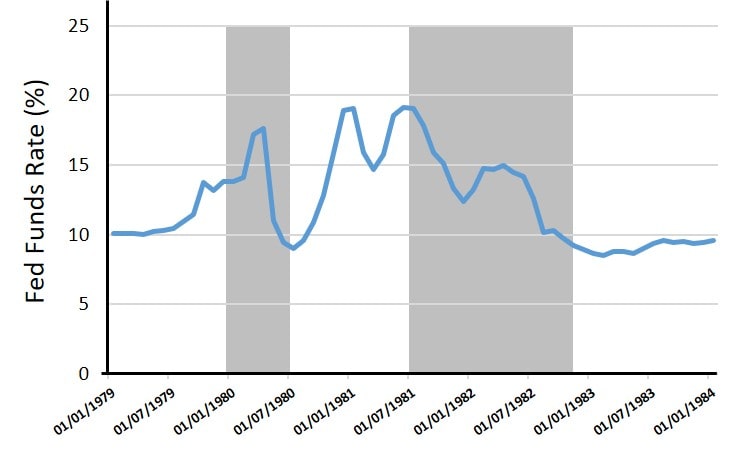

Federal Reserve interest rates during the late 1970s and early 1980s show that rates can rise during a recession when inflation remains high, as seen during the stagflation period.

Federal Reserve interest rates during the late 1970s and early 1980s show that rates can rise during a recession when inflation remains high, as seen during the stagflation period.A well-known example is the late 1970s and early 1980s period of stagflation in the United States and the United Kingdom. The chart above illustrates of the Federal Reserve set interest rate policy during this time. The two gray blocks indicate periods of recession; one in the first half of 1980, and one from mid-1981 until late-1982.

During this time, economic growth was weak and unemployment was rising, yet inflation remained persistently high due to supply shocks, loose monetary conditions in earlier years, and rising energy prices.

As can be seen, interest rates increased sharply as the economy deteriorated and entered recession in 1980, as the Fed was forced to prioritize restoring price stability over supporting short-term growth. This recession was not caused by falling demand alone, but by an aggressive tightening of monetary policy aimed at breaking inflationary expectations. By contrast, the longer recession from mid-1981 until late-1982 was met with interest rate cuts from beginning to end, because inflation was no longer a threat by that time.

This episode demonstrates that when inflation dominates the economic landscape, recessions can coincide with rising interest rates rather than falling ones.

More Recently

More recent history also shows how interest rates can behave in unexpected ways, even when central banks begin cutting policy rates. In some cases, cuts to short-term rates have been followed by rising long-term interest rates, particularly at the long end of the yield curve.

This can happen when markets interpret rate cuts not as a sign of easing inflation, but as a response to deeper structural problems. If investors believe that rate cuts will eventually lead to higher inflation, increased government borrowing, or prolonged fiscal deficits, they may demand higher yields on long-term bonds to compensate for future risk.

As a result, mortgage rates and long-term borrowing costs can rise even as central banks reduce short-term rates.

These mechanisms highlight the importance of expectations in determining interest rates during a recession. Policy rates influence the short end of the market, but long-term rates are shaped by beliefs about future inflation, debt sustainability, and economic stability.

When confidence in policy effectiveness is weak, or when inflation risks remain elevated, the usual relationship between recessions and lower interest rates can break down. Historical case studies like stagflation and recent yield-curve reversals illustrate why interest rates are not simply reactive to recessions themselves, but to the broader economic forces that surround them.

Impact on

Borrowers, Savers, and Markets

Shifts in interest rates during a recession affect different groups in different ways. While lower rates can reduce borrowing costs, they also change incentives, risk tolerance, and returns across the financial system.

- Borrowers: Lower interest rates usually reduce the cost of loans and mortgages, especially variable-rate debt. However, tighter lending standards during recessions can limit access to credit despite lower rates.

- Savers: Falling rates tend to reduce returns on savings accounts and certificates of deposit. This can discourage saving and push households toward riskier assets in search of yield.

- Investors: Lower rates can support bond and equity prices by reducing discount rates. At the same time, uncertainty and inflation expectations can lead to volatile market outcomes.

- Banks and Credit Markets: Lower rates often compress bank margins, which can reduce lending activity. Credit spreads may widen, limiting how much borrowers benefit from rate cuts.

Taken together, what happens to interest rates during a recession reshapes financial behavior across the economy, easing some pressures while introducing new constraints and risks.

FAQs

How quickly do

interest rates change after a recession begins?

How quickly do

interest rates change after a recession begins?

Interest rates do not adjust instantly when a recession starts. Central banks typically wait for confirming economic data, while markets may move in advance based on expectations. As a result, some rates can change before a recession is officially declared, while others adjust gradually over time.

Are interest rate

cuts more effective early or late in a recession?

Are interest rate

cuts more effective early or late in a recession?

Rate cuts tend to be more effective earlier in a recession, when credit markets are still functioning and confidence has not fully deteriorated. Later in a downturn, lower rates may have limited impact if businesses and households are unwilling or unable to borrow.

How do recessions

affect fixed-rate versus variable-rate loans?

How do recessions

affect fixed-rate versus variable-rate loans?

Variable-rate loans usually adjust more quickly when policy rates change, which can lower payments during a recession. Fixed-rate loans are locked in and do not change unless refinanced, meaning borrowers may not benefit from falling rates without taking additional action.

Do recessions change

how banks decide who gets credit?

Do recessions change

how banks decide who gets credit?

Yes, recessions often lead banks to tighten lending standards. Even when interest rates fall, lenders may become more selective, requiring higher credit scores, larger down payments, or more collateral to manage rising default risk.

Can government debt

levels affect interest rates during a recession?

Can government debt

levels affect interest rates during a recession?

High or rapidly rising government debt can put upward pressure on long-term interest rates. During a recession, increased borrowing to fund deficits may lead investors to demand higher yields, especially if inflation or fiscal sustainability is a concern.

How do global factors

influence interest rates in a domestic recession?

How do global factors

influence interest rates in a domestic recession?

Global capital flows, exchange rates, and foreign monetary policy can all influence domestic interest rates. In some cases, international demand for safe assets can push rates lower, while global inflation pressures can have the opposite effect.

Practical

Takeaways and Economic Implications

The most important takeaway from examining what happens to interest rates during a recession is that lower rates are common, but not guaranteed. Interest rates respond to incentives, expectations, and constraints, not to recessions in isolation.

Demand-driven downturns with falling inflation tend to create conditions where central banks can cut rates aggressively. Recessions driven by supply shocks, persistent inflation, or fiscal stress often limit that flexibility and can produce very different outcomes.

Another key implication is that not all interest rates matter equally.

Short-term policy rates are directly influenced by central banks, but long-term interest rates are shaped by market expectations about inflation, debt sustainability, and future policy credibility. This is why mortgage rates, bond yields, and savings rates can move in unexpected directions, even when central banks are easing. Rate cuts that signal economic weakness or future inflation risk can push long-term yields higher rather than lower.

For households, businesses, and investors, this means that interest rate changes during a recession should be interpreted as signals, not guarantees. Lower rates may ease debt burdens, but tight credit conditions, higher risk premiums, or rising long-term yields can offset those benefits.

In short, what happens to interest rates during a recession depends less on the recession itself and more on the forces behind it. Inflation expectations, policy credibility, and market confidence ultimately determine how interest rates adjust, and whether lower rates translate into real economic relief or new financial distortions.

Source:

Related Pages:

- Monetary Transmission Mechanism - Shows why interest rate cuts don’t always lower mortgage rates or business loan costs during a downturn.

- Liquidity Preference Theory - Explains why investors often push interest rates lower by moving into safe assets during economic uncertainty.

- Loanable Funds Theory - Helps explain why long-term interest rates can rise even when short-term rates are being cut.

- Debt Deflation Theory - Shows how falling incomes and asset prices during recessions can weaken the impact of lower interest rates.

- Liquidity Trap - Describes situations where interest rates are already low and further cuts fail to stimulate borrowing.

- Business Cycle - Places recessions and interest rate changes within the broader pattern of economic expansions and contractions.

About the Author

Steve Bain is an economics writer and analyst with a BSc in Economics and experience in regional economic development for UK local government agencies. He explains economic theory and policy through clear, accessible writing informed by both academic training and real-world work.

Read Steve’s full bio

Recent Articles

-

What Happens to House Prices in a Recession?

Jan 11, 26 03:13 AM

What happens to house prices in a recession? Learn how different recessions affect housing, why 2008 was unique, and how policy responses change home values. -

Does Government Spending Cause Inflation?

Jan 10, 26 06:01 AM

Does government spending cause inflation? See how waste, crowding out, and stimulus spending quietly push prices higher over time. -

What Happens to Interest Rates During a Recession

Jan 08, 26 05:31 PM

What happens to interest rates during a recession? Explore why rates often fall, when they don’t, and how inflation, policy, and markets interact. -

Circular Flow Diagram in Economics: How Money Flows

Jan 03, 26 04:57 AM

See how money flows through the economy using the circular flow diagram, and how spending, saving, and policy shape real economic outcomes. -

What Happens to House Prices During Stagflation?

Jan 02, 26 09:39 AM

Discover how house prices and real estate behave during stagflation, with historical examples and key factors shaping the housing market.