Are Tariffs

Deflationary? Understanding the Real Economic Effects

Are tariffs deflationary? Some commentators, most recently Jared Dillian, have argued that trade barriers, by slowing economic activity, can create downward pressure on prices.

At first glance, the idea has a superficial appeal: if consumers buy fewer goods because prices rise, overall demand falls, and perhaps the general price level declines. Yet this argument ignores the most basic principles of how prices and markets actually work.

Tariffs do not operate in isolation. They impose costs on production, distort resource allocation, and shift aggregate supply in ways that almost inevitably lead to higher prices for affected goods. To understand why the idea that tariffs are deflationary is flawed, it is essential to analyze the problem through the lens of the AD-AS Model, combined with an understanding of how markets coordinate via prices.

Tariffs as a

Supply Shock

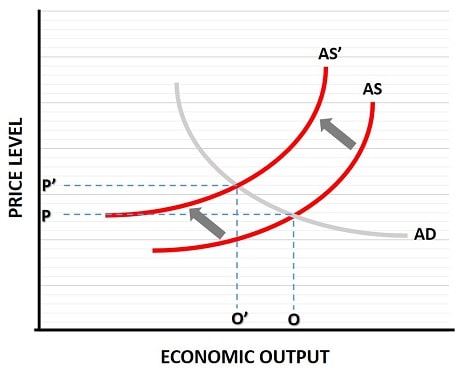

A tariff is, at its core, a tax on imports. When applied to essential goods, raw materials, or intermediate products, it directly raises the cost of production for domestic firms that rely on those imports. In macroeconomic terms, this is a leftward shift in the aggregate supply curve. For any given price level, firms are willing to produce less because their costs have increased.

Consider the example of the automobile industry. If a tariff increases the cost of imported parts or vehicles by 20 percent, the immediate effect is that producers must either absorb the higher cost, which reduces their margins, or pass it on to consumers in the form of higher prices.

The notion that this could somehow be deflationary assumes that consumers will immediately reduce their spending to such an extent that the overall price level falls, but this ignores the relative inelasticity of many goods and the reality that production costs drive prices upward even in the face of reduced demand.

The AD-AS Model makes this clear. When a tariff raises the cost of production, the AS (aggregate supply) curve shifts left while the AD (aggregate demand) curve remains stable, the new equilibrium occurs at a higher price level and lower output.

This is a textbook cost-push scenario. The economy contracts, yes, but it does so at higher, not lower, prices. Suggesting that tariffs alone are deflationary is to misread the interaction of supply costs and market prices.

Demand

Contraction Is Not Automatic

Proponents of the “deflationary tariff” argument often assert that rising prices automatically suppress aggregate demand enough to counteract the supply-side shock. While it is true that higher prices can dampen consumption for some goods, the aggregate effect on the economy is usually modest.

In the particular cade of tariffs, we could even argue that it is demand for imported goods that will fall, and that demand for domestic goods might even rise on the aggregate level. This is because consumers will wish to purchase domestic substitute goods instead of the now relatively expensive imported goods. If this does happen, it will actually have an inflationary effect rather than deflationary.

However, we should not repeat the same basic error that Jared makes by getting ahead of ourselves. Aggregate demand is influenced by many other broader factors, including income levels, monetary conditions, and fiscal policy. The temporary reduction in purchases of one category of goods, like imported cars or steel, does not immediately translate into a leftward shift of the entire AD curve.

Moreover, many of the goods subject to tariffs are industrial inputs rather than final consumer products. Reducing consumption of these inputs is not simply a matter of choosing to buy less; it can trigger malinvestment and inefficiency, as firms struggle to substitute domestic inputs or adjust production processes. This does slow the economy in the medium term, but it does not create downward pressure on general price levels.

Instead, it raises the cost of production for other goods and services, which ultimately puts upward pressure on prices elsewhere in the economy.

The

Misleading Case of Bond Yields

Jared has pointed to falling bond yields as evidence of deflationary pressure in the economy. However, bond yields are an imperfect proxy for inflation. Short-term yields respond not only to expectations of future growth and inflation but also to central bank monetary policy, global capital flows, and investor risk sentiment. A temporary decline in yields may reflect expectations of rate cuts or a “flight to safety” rather than an actual deflationary trend.

In contrast, GDP provides a direct (albeit flawed) measure of economic activity. For Jared to be correct about tariffs being deflationary then we need to see those tariffs cause a very significant contraction in aggregate demand, one significant enough to override the aggregate supply contraction. This would imply a very significant slowdown in economic output, perhaps even a recession, along with actual deflation. However, if the economy is growing (as it seems to have done since Trump imposed tariffs) and if inflation persists (as it certainly has since Trump imposed tariffs) then there is no evidence of this severe contraction in aggregate demand.

None of this is to say that recession is not imminent, but the causes of such things are far more complex and meaningful than any imposition of tariffs. For details see my main article about:

Whatever the truth is, it seems to be a significant error to use bond yields as evidence of anything when much more direct metrics are available.

Real-World

Evidence

Historical evidence supports the theory that tariffs are inflationary rather than deflationary. The Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act of 1930, for instance, raised duties on thousands of imported goods. Prices for many affected items increased, while the economy fell into a deeper recession.

While the Smoot-Hawley Tariffs of 1930 did raise duties on thousands of imported goods, the deflation observed during the Great Depression did not result from the tariffs themselves.

Instead, the deflation was largely caused by a catastrophic contraction of the money supply, banking failures, and collapsing credit. The tariffs added to the economic pain by raising production costs and reducing international trade, but they did not directly cause the falling general price level.

In fact, in sectors directly affected by tariffs, prices often rose as expected due to higher import costs, consistent with the cost-push inflation effect. The overall deflation was a macroeconomic phenomenon driven by monetary collapse and collapsing aggregate demand, not by trade barriers per se.

Similarly, recent tariff measures on steel, aluminum, and automobiles have led to higher prices for both inputs and finished goods in the United States. Commodity prices, supply chain disruptions, and retaliatory tariffs often exacerbate these effects.

FAQs

How do tariffs

interact with exchange rates, and can currency movements soften their

inflationary effects?

How do tariffs

interact with exchange rates, and can currency movements soften their

inflationary effects?

Exchange rates can offset part of a tariff’s impact. If the exporting country’s currency depreciates relative to the importing country’s currency, the cost increase from tariffs may be partially or fully neutralized. However, this depends on the elasticity of currency markets, the scale of the tariff, and monetary policy conditions. A weak exporter currency does not eliminate the underlying supply-side shock - it only masks it through cheaper nominal pricing.

Why do economists

consider tariffs a form of “resource misallocation”?

Why do economists

consider tariffs a form of “resource misallocation”?

Tariffs encourage production in industries where a country does not possess comparative advantage. This diverts labor and capital away from more efficient sectors toward less productive ones. Over time, this leads to lower productivity, higher production costs, and slower potential GDP growth. Even if domestic industries temporarily benefit, the economy becomes less efficient overall.

Can tariffs trigger

second-round inflation effects beyond the industries they directly target?

Can tariffs trigger

second-round inflation effects beyond the industries they directly target?

Yes. Tariff-induced cost increases in upstream industries (e.g., steel, semiconductors) cascade into downstream sectors such as automotive, construction, and consumer electronics. Firms facing higher input costs raise prices across multiple supply-chain layers, creating economy-wide inflationary spillovers beyond the originally targeted goods.

How do tariffs affect

wages and labor markets in protected industries?

How do tariffs affect

wages and labor markets in protected industries?

In the short run, protected industries may experience higher demand for domestic labor, which can push up wages. However, these wage increases often reflect artificial protection rather than productivity gains. Once protection expires or global conditions shift, these sectors may struggle to maintain wage levels or employment, leading to volatility in labor markets.

Do tariffs discourage

or encourage domestic capital investment?

Do tariffs discourage

or encourage domestic capital investment?

Tariffs can encourage investment in the protected sector, but they often discourage investment in the broader economy. Capital flows into less efficient industries because artificial price signals create a false sense of competitiveness. Investors may delay or avoid investments in sectors exposed to higher input costs or retaliatory trade policies.

How do retaliation

and counter-tariffs affect domestic inflation dynamics?

How do retaliation

and counter-tariffs affect domestic inflation dynamics?

Retaliatory tariffs raise costs for exporters, reducing their foreign demand and sometimes forcing domestic price adjustments. Additionally, counter-tariffs often target politically sensitive sectors (agriculture, autos, or industrial goods) leading to income losses in those sectors that ripple through the broader economy. These effects can raise prices in some areas while depressing output in others, increasing economic inefficiency.

Conclusion

The argument that tariffs are deflationary is appealing on the surface but fails under closer scrutiny. Tariffs increase production costs and shift the aggregate supply curve leftward, leading to higher prices and lower output — the textbook definition of a cost-push shock.

Aggregate demand does not automatically collapse to offset the price increases, and temporary movements in financial markets such as bond yields cannot substitute for real economic data. Historical examples confirm that tariffs tend to create inflationary pressure in affected sectors, even if they slow overall growth.

For anyone evaluating trade policy, it is necessary to distinguish between an economic slowdown and falling prices. Tariffs slow growth and distort markets, but they do not inherently produce deflation. The real-world consequences are higher prices, reduced efficiency, and misallocated resources.

The next time someone asks, “Are tariffs deflationary?” the answer is clear: no, tariffs are not deflationary. They increase costs, distort markets, and, in the aggregate, lead to higher prices. Any slowdown in the economy is a side effect, not a price-reducing mechanism.

Sources:

Related Pages:

- Demand Destruction - Relevant because Jared’s argument hinges on this concept.

- Imported Inflation - Tariffs explicitly raise import prices, feeding into domestic inflation.

- Stagflation - The scenario that results when output falls and prices rise—tariff effects resemble this.

- Net Exports Effect - Tariffs disrupt trade flows, influencing GDP via exports and imports.

About the Author

Steve Bain is an economics writer and analyst with a BSc in Economics and experience in regional economic development for UK local government agencies. He explains economic theory and policy through clear, accessible writing informed by both academic training and real-world work.

Read Steve’s full bio

Recent Articles

-

What Happens to House Prices in a Recession?

Jan 11, 26 03:13 AM

What happens to house prices in a recession? Learn how different recessions affect housing, why 2008 was unique, and how policy responses change home values. -

Does Government Spending Cause Inflation?

Jan 10, 26 06:01 AM

Does government spending cause inflation? See how waste, crowding out, and stimulus spending quietly push prices higher over time. -

What Happens to Interest Rates During a Recession

Jan 08, 26 05:31 PM

What happens to interest rates during a recession? Explore why rates often fall, when they don’t, and how inflation, policy, and markets interact. -

Circular Flow Diagram in Economics: How Money Flows

Jan 03, 26 04:57 AM

See how money flows through the economy using the circular flow diagram, and how spending, saving, and policy shape real economic outcomes. -

What Happens to House Prices During Stagflation?

Jan 02, 26 09:39 AM

Discover how house prices and real estate behave during stagflation, with historical examples and key factors shaping the housing market.