- Home

- Fractional Reserve Banking

- Money Illusion

Money

Illusion Controversies Explained (with Graphs)

The term ‘money illusion’ describes the tendency of individuals, firms, and even governments to think in nominal rather than real terms e.g., to mistake rising numbers for genuine prosperity. When prices rise alongside wages, many still feel richer. When monetary policy expands the quantity of money, rising nominal GDP can be mistaken for real growth.

This confusion between money and wealth has shaped macroeconomics for nearly a century. From the Keynesian justification for active demand management to the Austrian critique of credit expansion, and ultimately to the rational expectations insight that illusions cannot last forever, the story of money illusion is the story of how modern economies oscillate between profligacy and reckoning.

In what follows, we’ll trace the intellectual evolution of the concept, how it influenced postwar policy, why the Austrian school has always distrusted it, and how the logical endpoint of persistent money illusion is the collapse of confidence in money itself i.e., the hyperinflationary finale when the illusion dies.

Origins and Historical Context

The phrase money illusion entered the economic lexicon through Irving Fisher’s 1928 book The Money Illusion, though the idea itself was implicit in much earlier monetary theory. Fisher observed that people fail to distinguish between nominal and real values; that “a man thinks himself richer when he gets more money, though prices rise in equal measure.”

This insight had clear empirical relevance in the early 20th century, when economies experienced alternating bouts of inflation and deflation. During the 1920s and 1930s, price-level instability and mass unemployment led economists to ask why labor markets failed to clear. Classical theory predicted that falling prices and wages should restore equilibrium; yet wages proved “sticky” downward.

John Maynard Keynes, writing during the Great Depression, offered an explanation: workers resist nominal wage cuts even if real wages have already risen because of falling prices. In The General Theory (1936), Keynes argued that money illusion was a key source of labour-market rigidity. Since workers negotiate in money terms, not in units of goods, nominal wages adjust slowly.

This small behavioral quirk, the tendency to think in nominal magnitudes, became the cornerstone of Keynesian macroeconomics. It justified government intervention: if prices and wages don’t adjust quickly, then fluctuations in aggregate demand can cause real output and employment to fall below potential. Monetary policy and fiscal policy, by increasing nominal spending, could therefore eliminate cyclical unemployment.

Money illusion, in short, was what made Keynesian stimulus possible.

The

Mainstream (Keynesian and New-Keynesian) Perspective

Mainstream economics treats money illusion as a temporary cognitive or informational imperfection that allows nominal shocks to have real effects.

Labor Market

Implications

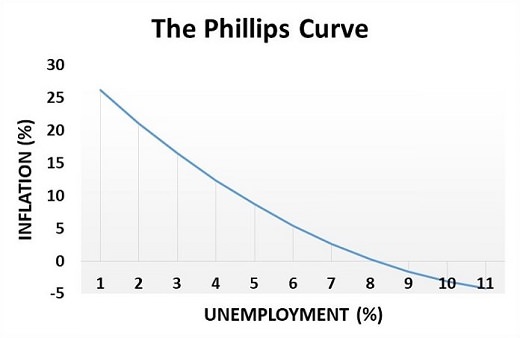

Workers fixate on nominal pay. They perceive a 5 % nominal wage cut as a loss, even if prices fall by 10 %. Conversely, they may accept a 5 % nominal wage rise even if prices rise 10 %, because they notice the higher wage more than the diminished purchasing power. This “wage illusion” helps explain persistent unemployment during deflations and the apparent ability of inflation to reduce joblessness i.e., the short-run Phillips Curve relationship.

The Keynesian short-run tradeoff between inflation and unemployment.

The Keynesian short-run tradeoff between inflation and unemployment.The Policy

Mechanism

If people evaluate outcomes in nominal terms, policymakers can influence real output by manipulating nominal aggregates. A central bank increasing the money supply can lower real wages (since prices lag behind wages), stimulating hiring and production. Likewise, governments can boost nominal demand through deficit spending, encouraging firms to expand output before prices fully adjust.

This logic underpinned the Keynesian revolution and postwar demand management. By accepting some inflation, policymakers could maintain higher employment and smoother growth.

Long-Run

Neutrality

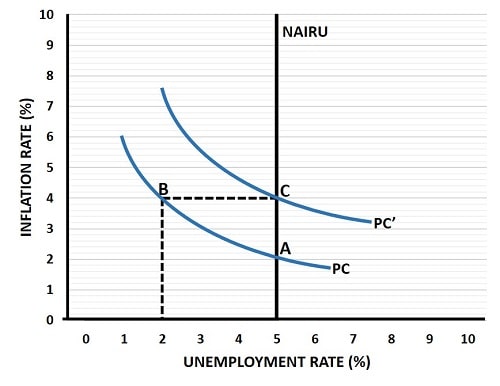

Over time, however, people learn. As expectations adjust, the illusion fades. Workers demand wage increases that compensate for expected inflation; lenders and borrowers incorporate inflation expectations into interest rates. The short-run trade-off between inflation and unemployment disappears, and money becomes neutral in the long run.

Still, for several decades after World War II, most governments accepted that exploiting short-run money illusion was a legitimate tool for macroeconomic stabilization.

Post-1971:

The Fiat-Money Era and Institutionalized Illusion

The collapse of the Bretton Woods system in 1971, when President Nixon suspended dollar-gold convertibility, transformed the monetary landscape. For the first time, major currencies were pure fiat instruments, unconstrained by convertibility or commodity backing as representative money had been prior to 1971.

This new regime gave central banks freedom to expand money and credit to manage domestic objectives. Inflation targeting replaced gold discipline; demand management became institutionalized.

Inflation as

a "Lubricant"

Mild inflation came to be seen as socially useful. It allowed nominal wages to rise even when real wages stagnated, helping to avoid confrontations over wage cuts. It also eroded the real value of public and private debt, reducing the political pain of deleveraging. Economists began to speak of a “menu cost” or “expectations-augmented Phillips curve”, assuming that small, steady inflation could stabilize employment.

In the long-run, a new Phillips Curve emerges and the inflation/unemployment tradeoff disappears.

In the long-run, a new Phillips Curve emerges and the inflation/unemployment tradeoff disappears.Asset

Markets and the Wealth Effect

Meanwhile, expanding money and credit inflated asset prices (housing, equities, bonds) creating the appearance of rising wealth. Nominal portfolio gains encouraged consumption and borrowing, reinforcing aggregate demand. This was the macroeconomic embodiment of money illusion: rising numbers on balance sheets stood in for real gains in productivity or income.

The Great

Moderation

From the mid-1980s to the early 2000s, advanced economies enjoyed relatively stable growth and low inflation, a period economists called the Great Moderation. Many attributed it to improved central-bank policy. Critics, especially from the Austrian tradition, warned that it was an illusion, it was stability purchased through credit expansion, destined to end in crisis.

They were vindicated in 2008, when the illusion unraveled.

The Austrian

Economics Counter-View

For the Austrian School, money illusion is not just a cognitive bias but a systemic deception embedded in the modern monetary order.

The Deeper

Illusion

In Austrian business-cycle theory (ABCT), articulated by Ludwig von Mises and Friedrich Hayek, interest rates coordinate intertemporal plans: they reflect real savings and time preference. When central banks artificially lower rates by expanding credit, they create the illusion that more real savings exist than actually do. Entrepreneurs undertake long-term investments that cannot be sustained.

This is money illusion in structural form, not a misunderstanding by individuals but a mispricing of time and capital throughout the economy. Nominal expansion masks the absence of real savings, and the link between saving and investment described by Neoclassical growth theory e.g., the Solow Growth Model, is broken.

Policy

Illusion as Cause of Cycles

While Keynesians see money illusion as a reason for stabilization policy, Austrians see it as the source of instability. Every attempt to paper over economic weakness with new credit or inflation deepens misallocation. What mainstream economics calls “stimulus,” Austrians call “malinvestment.”

From Gold to

Credit

The gold standard, in Austrian eyes, constrained illusion by tying money to real scarcity. Once gold convertibility was abandoned, monetary expansion could proceed indefinitely. Prices, wages, and asset values rose, and societies mistook nominal gains for genuine progress. The apparent prosperity of the fiat era, Austrians argue, is built on cumulative money illusion – a pyramid of claims unbacked by real savings.

The

Reckoning

Eventually, reality reasserts itself. When the flow of new credit slows or inflation accelerates beyond expectations, the illusion collapses. Capital values fall, projects fail, and recession clears out malinvestment. The “boom” is revealed to have been a redistribution of wealth through inflation rather than real growth.

Has Money

Illusion Smoothed or Destabilized the Cycle?

The mainstream narrative holds that money illusion has helped to smooth the business cycle. By allowing moderate inflation to erode real wages and debt burdens, policymakers can cushion recessions and promote steady demand. The cost, a little inflation, seems worth the stability gained.

The Austrian counter-narrative flips this logic. What looks like stabilization is merely the masking of imbalances. Each new round of stimulus adds another layer to the illusion: higher nominal debt, inflated asset prices, and a widening gap between paper wealth and productive capacity. When that illusion fails, as in 2008 and arguably again after the monetary expansions of 2020-2022, the adjustment is far more severe.

The historical record since 1971 offers evidence for both views: shorter, shallower recessions offset by longer-term build-ups of debt and fragility. Whether that counts as success or failure depends on one’s tolerance for illusion.

The Endgame

of Money Illusion: Rational Expectations and Hyperinflation

If governments and central banks persist in expanding money and credit to sustain nominal prosperity, a limit is eventually reached and people stop being fooled.

Rational

Expectations and the Death of Surprise

The rational expectations revolution of the 1970s, led by Robert Lucas and Thomas Sargent, formalized this idea. Agents, they argued, are not perpetually naïve. They learn from experience and form expectations consistent with the underlying structure of the economy. If monetary authorities pursue a predictable inflationary policy, rational agents will anticipate it.

When that happens, money illusion collapses. Increases in the money supply lead to immediate price adjustments, leaving real output unchanged. The short-run trade-off between inflation and unemployment disappears. Monetary policy becomes ineffective except insofar as it surprises people – a trick that can’t be repeated indefinitely.

Hyperinflation

as the Final Stage

In extreme cases, this process culminates in hyperinflation, the real-world manifestation of rational expectations. As inflation accelerates, people no longer treat money balances as wealth but as a hot potato to be exchanged instantly for goods. The velocity of money rises sharply and prices adjust in real time to new credit creation.

In Weimar Germany (1923), the Zimbabwean dollar (2008), and Venezuela’s bolívar (2010s), the pattern was the same; governments attempted to sustain spending and employment through monetary expansion, relying on lingering money illusion. At first, it “worked” and nominal activity rose. But as the public learned, each increase in money supply was matched, or exceeded, by price increases.

The illusion died. People ceased to think in money terms at all, reverting to barter, foreign currencies, or tangible goods. At that point, not only does monetary policy lose traction; money itself loses meaning.

The

Rational-Expectations Vindication

Hyperinflation, then, is not merely a fiscal failure. It is the logical conclusion of sustained money illusion. A system that depends on deception must eventually exhaust it. Once expectations are fully rational, that is, when everyone anticipates that more money means less purchasing power, there can be no further illusion, and no further policy leverage.

In this sense, the rational expectations school and the Austrian school converge. Both foresee a limit to the effectiveness of nominal manipulation, though for different reasons. The Austrians stress real-capital distortion while the rational-expectations theorists stress informational adaptation. But the end state is the same, money illusion dies, and monetary policy dies with it.

Integrating

the Three Traditions

Across nearly a century of theory, the concept of money illusion traces a full intellectual arc:

- Keynesian Phase: Money illusion makes nominal policy effective; it justifies government stabilization.

- Austrian Phase: Money illusion is the root of artificial booms and busts; monetary expansion creates misallocation, not real growth.

- Rational-Expectations Phase: As agents learn, money illusion disappears; policy loses real influence, and persistent expansion leads to inflation or hyperinflation.

The progression is almost evolutionary; economies learn from their illusions until the deception can no longer function. Yet each generation seems to forget, rebuilding the illusion under new forms, from Bretton Woods to fiat money, from quantitative easing to digital liquidity.

Ultimately, both Austrians and rational-expectations theorists point toward the same conclusion i.e., real wealth cannot be printed. Monetary policy can redistribute and reprice, but it cannot create real capital, labor, or productivity. Once society recognizes this, whether through gradual disillusionment or sudden hyperinflation, the age of money illusion ends.

FAQs

How does money illusion affect investment decisions?

How does money illusion affect investment decisions?

Money illusion can lead investors to misinterpret nominal gains as real wealth, prompting over-investment in projects that appear profitable in nominal terms but may not generate real returns once inflation is accounted for. This is particularly relevant in credit-driven booms, where artificial liquidity masks underlying resource constraints.

Can money illusion

influence consumer spending patterns?

Can money illusion

influence consumer spending patterns?

Yes. Consumers may feel wealthier when nominal incomes or asset values rise, even if inflation erodes real purchasing power. This can temporarily boost consumption, creating a short-run stimulus effect before real constraints reassert themselves.

Does money illusion

impact wage negotiations?

Does money illusion

impact wage negotiations?

Absolutely. Workers often focus on nominal wages rather than real wages, resisting cuts even in deflation and accepting raises even when real purchasing power stagnates. This can reinforce wage stickiness and affect labor market dynamics.

Can money illusion

contribute to asset bubbles?

Can money illusion

contribute to asset bubbles?

Yes. When people interpret rising nominal asset prices as real gains, they may over-leverage or speculate excessively. This misperception amplifies credit cycles and can inflate bubbles in housing, equities, or other markets.

Can money illusion

persist in highly transparent financial systems?

Can money illusion

persist in highly transparent financial systems?

It can persist, but transparency and indexed contracts reduce its effects. Modern markets with inflation-indexed wages, adjustable-rate loans, and price-aware consumers diminish the magnitude of money illusion over time.

Conclusion:

The Age of Disillusion

The concept of money illusion is not an intellectual curiosity; it is the psychological and institutional foundation of modern macroeconomics. It explains why inflation can “work” in the short run, why fiat regimes can sustain decades of apparent prosperity, and why those same regimes eventually reach crisis points where nominal and real diverge catastrophically.

From Keynes to Hayek to Lucas, each generation of economists has wrestled with the same paradox: can illusions be managed indefinitely, or must they eventually collapse?

In the decades since 1971, the world has chosen management over discipline, leaning on the ability of central banks to conjure nominal growth from credit and belief. Yet history suggests that confidence, once lost, is nearly impossible to restore. When the public ceases to believe that money measures value, the illusion dies, and with it the ability to stabilize the economy through monetary tricks.

The end of money illusion may come gradually, through inflation expectations rising faster than central banks can adjust; or suddenly, through a collapse of faith in fiat currencies. Either way, it marks the return of economic realism, the recognition that true prosperity rests not on the quantity of money, but on the productive use of real resources.

Understanding money illusion is therefore not merely an academic exercise. It is a guide to the psychology of modern finance, the cyclical dance of policy and perception, and the ultimate limits of a system built on nominal promises. When the illusion fades, what remains is the enduring economic truth: real wealth cannot be faked.

Related Pages:

- Seigniorage – Governments’ incentive to create money and rely on public money illusion to finance spending through inflation taxation.

- Liquidity Trap – A Keynesian setting where money illusion may persist despite monetary expansion failing to stimulate real output.

- Real Balance Effect – The Pigou effect, where real wealth perceptions (and their distortion under money illusion) affect consumption.

- Debt Deflation Theory – Fisher’s companion idea: when money illusion reverses, falling prices increase real debt burdens.

- Creeping Inflation – A policy-sustained, moderate inflation rate that quietly relies on continued mild money illusion.

- Stagflation – Historical proof that persistent inflation can coexist with stagnation, undermining Keynesian reliance on money illusion.

About the Author

Steve Bain is an economics writer and analyst with a BSc in Economics and experience in regional economic development for UK local government agencies. He explains economic theory and policy through clear, accessible writing informed by both academic training and real-world work.

Read Steve’s full bio

Recent Articles

-

What Happens to House Prices in a Recession?

Jan 11, 26 03:13 AM

What happens to house prices in a recession? Learn how different recessions affect housing, why 2008 was unique, and how policy responses change home values. -

Does Government Spending Cause Inflation?

Jan 10, 26 06:01 AM

Does government spending cause inflation? See how waste, crowding out, and stimulus spending quietly push prices higher over time. -

What Happens to Interest Rates During a Recession

Jan 08, 26 05:31 PM

What happens to interest rates during a recession? Explore why rates often fall, when they don’t, and how inflation, policy, and markets interact. -

Circular Flow Diagram in Economics: How Money Flows

Jan 03, 26 04:57 AM

See how money flows through the economy using the circular flow diagram, and how spending, saving, and policy shape real economic outcomes. -

What Happens to House Prices During Stagflation?

Jan 02, 26 09:39 AM

Discover how house prices and real estate behave during stagflation, with historical examples and key factors shaping the housing market.